Sell Out, A Series: 5 Questions with Cheyenne Rain LeGrande ᑭᒥᐊᐧᐣ

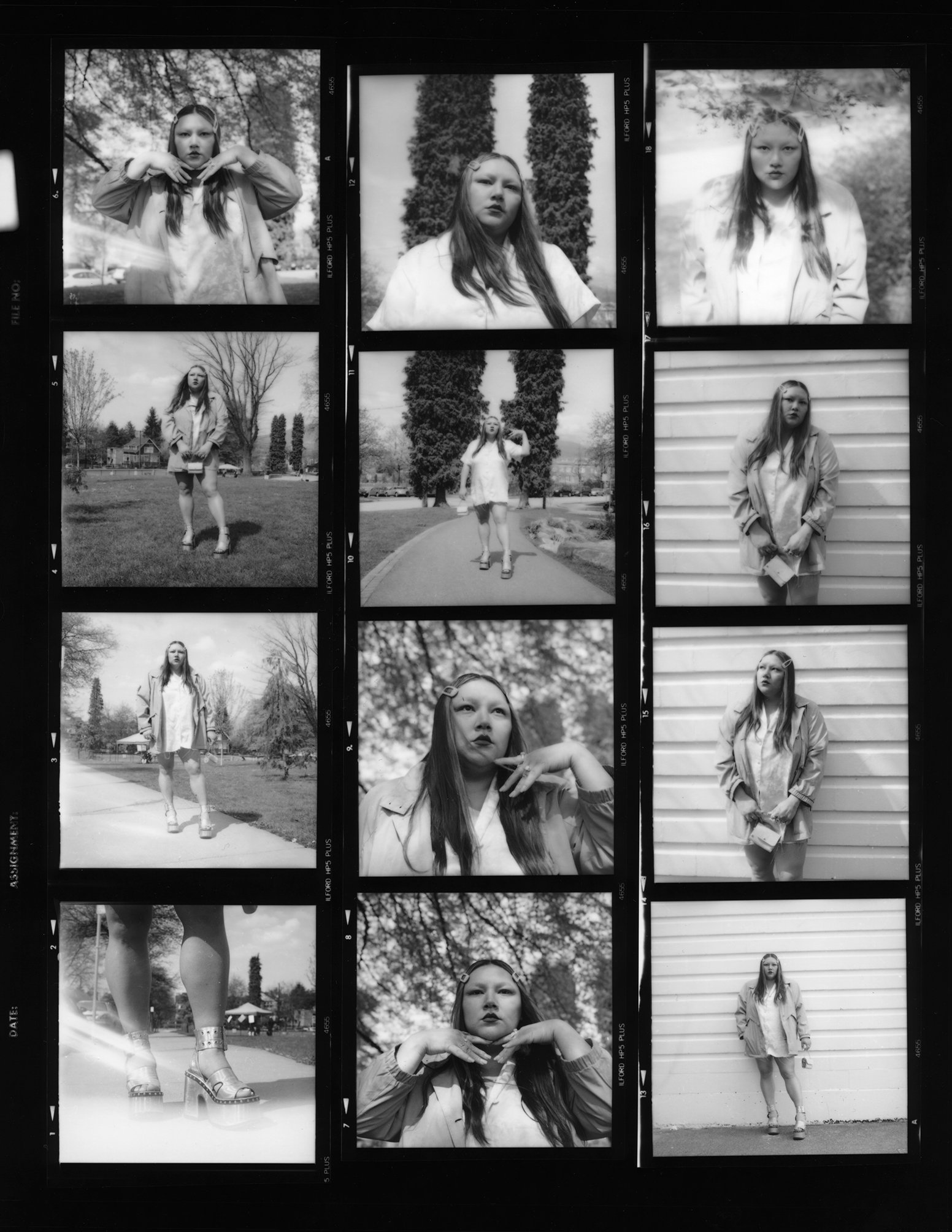

/Sell Out is a series by interdisciplinary artist Angela Fama (she/they), who co-creates conversations with individual artists across Vancouver. Questioning ideas of artistry, identity, “day jobs,” and how they intertwine, Fama settles in with each artist (at a local café of their choice) and asks the same series of questions. With one roll of medium format film, Fama captures portraits of the artist, after the verbal conversations have been had.

Cheyenne Rain LeGrande ᑭᒥᐊᐧᐣ (she/her) is a Nehiyaw Isko artist from Bigstone Cree Nation. Follow her work on Instagram @cheyennerainlegrande.

Location: Turks Coffee Bar

What do you make/create?

I am a Nehiyaw Isko, a Cree woman. My main focus is performance art, but I work interdisciplinarily between photography, video, sound, and installation. Often, I’ll take my performances and create an installation with them. I often work with my mother, her music and singing. Recently, I’ve been pushing myself to create my own sound. One of my really big goals is to create a Cree pop album with the help of my Nimama. I want to slowly introduce that into my performance practice by writing a song with my Nimama, and then having that be a part of the performance and tour it around.

My performance work, and work in general, comes from my expression of being an Indigenous woman. I’ve been working in traditional practices and reclaiming them. Recently, I did a Banff Centre residency where I created a fancy shawl out of pop and beer can tabs, weaving them together with ribbon. Fancy Shawl is a traditional pow-wow dance from my territory. It’s important for me to imbed my identity with what I create. I wasn’t raised around traditional dances, so I felt like being able to reuse an object, and recycle it, spoke to how I would create a fancy shawl if I could. It also felt like armour, because it’s made of aluminum.

What do you do to support that?

When I think of the word support, I think of family and community. As artists, obviously we still have to make money to survive, but for me having those connections often are a big support. Coming from a family where my brother’s a fashion designer, my Nimama’s a singer, my younger brother’s a model… we’re all very creative. That is the biggest support to me.

The more financial side is stuff like grants and residencies. The Banff Centre residency was my first residency. It was really great to do that, be a part of that. It was a really big support, having those types of opportunities.

Just this year, I decided to fully invest in being an artist, so I am not currently “working.” Since I graduated from Emily Carr, I have been working for different art institutions, and that was great, and I loved that experience, but it took a lot out of me, and I wasn’t creating. So, this year, I decided to go for it. That’s really exciting, a little bit scary [laughs], but exciting.

As well, I am really privileged in having my partner support me and am able to fully invest in art because of him. Yeah, that’s what support means to me: family, community.

Also: sharing knowledge. If I see a call, sharing that with art folks in my life. That’s really important too. There’s often a lot of opportunities that you don’t hear about. After the Banff Centre, because we were all around each other – someone was from Chicago, someone was from New Zealand – there are now opportunities to share connections outside of Canada.

When I think of support, I also think of mentorships. When I graduated from Emily Carr in 2019, I did a mentorship with Rebecca Belmore. That was an incredible experience. Again, shared knowledge was really important. Right now, I’m doing one with NIMAC with Tania Willard. Having that type of support too, to have other Indigenous people to look up to and learn from is a great support.

Describe something about how your art practice and your “day job” interact.

That’s hard to answer, because I currently don’t have a “day job.” When I did have a day job, I learnt that having a day job, even if it was in the arts, it took away a lot from being able to create. There’s an interesting conversation that I’m hearing a lot about art and work, and art being work, and the intersection between those two things. It was hard, really hard to create artwork while working. It’s almost as though you have two jobs. One to live, and the other to create.

For me, being able to just create work is…I think about the generations before me. I think about my Nimama, and I think about my Kokum, and I think about how in my generation, I’m able to just express, feel, and heal from a lot of trauma and things that we’ve been through. It’s a weird thing, because that’s work too. It’s a journey. To be able to do that, I feel so lucky and thankful that I’m in a generation where I have the opportunity to express and process through art. Nimama has always used her art and music as a way to express and heal, and she is such an inspiration to me.

What’s a challenge you’re facing, or have faced, in relation to this and/or what’s a benefit?

The challenge is sometimes being an Indigenous woman, but then also getting to express that: reclaiming traditional practices that I feel like have been lost, using my Nehiyaw language in my work. My Kokum and my Nimama both speak it, but I don’t. That’s also really hard. That’s something I’ve struggled with in my practice a lot. When I lived in Vancouver (currently I live in Amiskwaciy Waskahikan, also known as Edmonton, Alberta), when I was really going through something, and I was trying to express how I was feeling, I couldn’t find the words. I realized I didn’t have them. I didn’t have access to the words to express how I was feeling. When I hear my Nimama, or my Kokum speak, when I hear what a word means, it makes more sense to me than an English word, but I don’t have access to it.

That’s why I always try to incorporate language into my practice, so that I can slowly learn. Even if it’s just a title for my artwork, I know that word now. I know what it means. Like when I go visit my Kokum, she’ll teach me random words. It can really hurt to have lost things. But then it’s also really beautiful to get to reclaim them and be here and now, and still be here.

Have you made or created anything that was inspired by something from your day job? Please describe.

My most recent “day job,” which was the Banff residency, inspired the performance I did at the end of it, because it is so beautiful there. It’s similar to being in Vancouver, where it’s not my territory. Trying to understand that, and what that means as an Indigenous person, to be there when it’s not my territory, surrounded by all this beauty. I’d wake up every morning, so thankful to be there. There’s deer walking around everywhere. It was so magical. I was always filming on my phone, and everything that I filmed – the mountain, trees, water – I projected onto my body when I performed. For me, that was a way to acknowledge the land and be thankful. That really inspired me. Everyday life inspires me. I keep going back to feeling very thankful to just be here.

In the fall, at the end of September, I’m going to have my first solo show. It will be in Vancouver at Grunt Gallery. That’s very exciting, and what I’ll be working on for the next little bit. My Fancy Shawl will be a part of it, and I’m going to create another object for it that I’ll perform with. I’ll take the Fancy Shawl back home and perform with the water and the sunset, because the sunsets in Wabasca are just so beautiful.

Angela Fama (she/they) is an artist, Death Conversation Game entrepreneur, photographer, musician, previous small-business server of many years (The Templeton, Slickity Jim’s etc.). They are mixed generation settler currently working on the unceded traditional territory of the Coast Salish xʷməθkwəy̓əm, Skwxwú7mesh and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh Nations.

Follow them at IG @angelafama IG @deathconversationgame or on their website www.angelafama.com