Walking the Garden with Asia Jong

/to carve without cutting

Exhibited by UNIT/PITT Society for Art and Critical Awareness, Asia Jong’s exhibition, to carve without cutting, features eight artist couples: Qian Cheng & Chris Lloyd, Barry Doupé & Dennis Ha, Maria-Margaretta & Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley (featuring Mino-Margaret Cabana Boucher Pawis Steckley), Ellis Sam & Tiziana La Melia, Dana Qaddah & karmella benedito de barros, Amy Ching-Yan Lam & Robin Simpson, Lou Lou Sainsbury & Gabi Dao, and Erin Skiffington & Landon Lim.

Photography by Dax Heaven & Dennis Ha

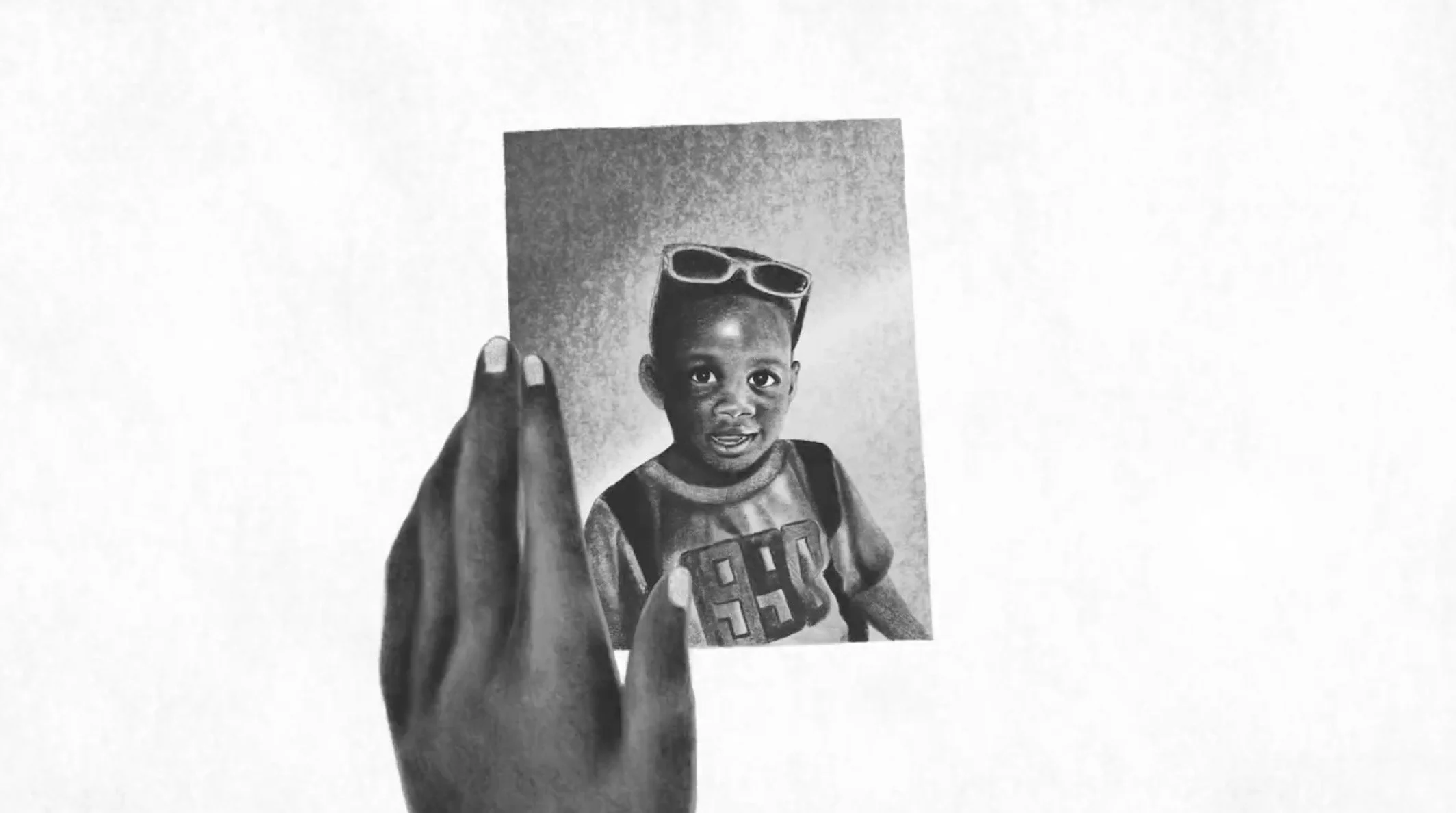

asia jong in 'to carve without cutting' exhibition at sun-yat-sen garden. photography by dax heaven.

Asia Jong is a curator who has flowered roots in Chinatown. For the first two years after she moved here, she never left. Her work feels like a love letter to this place. As a diasporic Chinese settler herself, Asia is attuned to the nuances of this deeply political, ever-changing community. At the core of her curatorial practice is people – and a way of being in relation that is as malleable, dynamic, and fluid as water. Her earlier works invite audiences to thoughtfully create relations to Chinatown, sending you searching for the color gold down Pender St, or offering cheap date ideas in Chinatown that are tenderly allusive to the intimacies of her own memories.

Located in the Dr. Sun-Yat Sen Classical Chinese Garden and Public Park in Chinatown, her most recent exhibition, to carve without cutting, is weaved into and inseparable from the historic garden. It’s a brisk autumn morning, and I’m observing the erosion in the Taihu rocks in the Sun-Yat Sen Garden when, flitting down the corridor like a hummingbird, Asia zips by. In her shoulder bag, a rolled newspaper–also a part of the exhibit–sticks out cartoonishly. She doesn’t see me. I call out her name, “Asia!”

I joke that I wasn’t sure if I was supposed to find her in the maze of the garden, like viewers are intended to find the artworks exhibited throughout the garden space – was this hide and seek a part of the exhibition tour? Looking with intention is deeply embedded in to carve without cutting. Artworks by eight romantically involved artist couples are mapped throughout the Sun-Yat Sen Garden and Park–some swaying from the branches of willow trees, others clandestinely nestled into earth or rockfaces, blending into the gardenscape.

Separated by two entry points, one side is the private garden, and the other is the public park; distinct from each other but connected by the pond. Viewers are asked to observe, walk around, and interact with the exhibition. Looking across the waters from either side of the garden gives a sense of harmony and grandeur, but depending on your vantage point, one can find new perspectives. “There is not really a specific way to navigate the show [or a] predestined path,” Asia explains, gesturing as she walks. There’s a sense of spaciousness in Asia Jong’s curatorial practice; an airy effervescence filled with possibility for what the garden and viewers may contribute; a quality of lightness grounded by conviction in relationality.

Over the two years that she has worked on to carve without cutting, she has gotten to know the garden very well. She tells me she’s fixing the exhibition; something she’s been doing regularly over the past month. The technical challenges of setting up the exhibition in an outdoor park have been generous–from navigating the layers of institutional permits to artworks being stolen by wildlife just hours before opening reception. But Asia seems to mend these technicalities with not only great care, but also with diligence and an assured acceptance of the inevitability of such challenges, even sticky-fingered raccoons.

Qian Cheng and Chris Lloyd, Caution in the Wind, 2024, plexiglass, wood, canvas, graphite and charcoal on paper, found objects, speaker, 37 x 15 x 15 inches, to carve without cutting, 2024. Photography by Dennis Ha.

Asia Jong: I got an email from the garden with the subject heading “Raccoon Hooligan”... A raccoon had taken the box [for the work Caution in the Wind by Qian Cheng & Chris Lloyd] and had opened it up and splayed out all of the stuff, including the speaker and iPhone inside. When you're working in this type of environment, it's truly like you have no idea what's gonna happen.

How did the outdoor exhibition space, Sun-Yat Sen Garden, influence to carve without cutting?

AJ: The garden is a replica of a Ming Dynasty era scholar’s garden. Everything in the garden is extremely laden with symbolism. I was really inspired by the design and the principle of the garden, which is around yin and yang. Historically, there's so many elements that are attributed to both yin and yang. So for example, water is usually attributed to yin, and rock is usually attributed to yang.

What interests me the most is the fluid nature of both. The misconception is that they're opposites, yes, but in reality, they're inseparable and intertwined, and they're completely non-binary. The yin and yang [are] constantly switching. For example, I take the metaphor of the Taihu rock. In the pond, the water is soft and flowing against the rock, and the rock is what is hard. The water is what's yielding. But as soon as you get water moving in a canyon or in a river, all of the sudden the water is what becomes a piercing force, and the rock becomes what’s soft and yielding, so the rock gives way to the water, and it's in that instance that yin becomes yang, and yang becomes yin.

How do yin and yang appear in to carve without cutting?

AJ: I wanted to do a show about romantic love, so I asked eight different romantically involved artist partners to create collaborative artworks together for the site specificity of this garden and park. Two of them have a child together, and one of them, they're in the process of uncoupling and breaking up. And then there's another couple that hadn't even met before. They were a complete online romance. They collaborated on the artwork individually, and they didn't meet until the opening night.

to carve without cutting – I really wanted to allude to ideas from the Tao Te Ching, and think about the way in which energy and flow is a natural occurrence. We can't force each other to change for ourselves or for each other. We just have to let our energies intertwine and harmonize in a way that allows for growth and change.

Ellis Sam and Tiziana La Melia, Transparency, 2024, PVC, glass, paint, love, 10 x 39 x 39 inches, to carve without cutting, 2024. Photography by Dennis Ha.

What is your relationship to the exhibition’s location, to Chinatown?

I'm originally from the Okanagan Valley, and I moved here six years ago to work at Centre A. My mom and all of her family were, actually, born in my small town, Armstrong. It's a very small rural town. Growing up in a town where there’s little to no representation of your culture or your heritage, I just feel there's always this breaking point that's like, I just am so sick of having to explain myself or trying to find somebody to relate to. That's why places like Chinatown are so important, especially for diaspora, because you're trying to reconnect, or you're trying to find the missing pieces, or trying to figure something out about yourself that maybe you haven't before. So I think that's why I was like, I'm getting out of this fucking white city. I'm moving to Chinatown. For the first two years that I moved here, I would not leave this neighborhood. Because I didn't want to go anywhere else, and everything felt so far, and I just really felt at home here.

Something that really drew me towards this exhibition was how community-oriented it is. It’s free, accessible; it’s outdoors.

Amy Ching-Yan Lam and Robin Simpson, The Pond, 2024, digital print on oilcloth, dimensions variable. Photography by Dennis Ha.

It was really important to me that the show was free because I really want it to be as accessible as possible, so people could just walk into the park and see some works floating in the pond, and be like, what's that? Truly, I feel like my projects and my curatorial practices are all centered around relationships. I feel like the only reason I really do anything is just to make a new friend.

I've always been interested in facilitating other people's relationships, or trying to, you know, elicit something new in a relationship that already exists. So that's sort of what I thought would be interesting from this project, because a lot of these artists never work together in artistic partnership. Some of them do. Some of them collaborate a lot, yeah. But through this exhibit, they've collaborated in new ways, or are just starting to. Like, it's an impetus to start collaborating. So, yeah, friendship and relationship building has always been the core of why I am interested in doing any of this art stuff. It sounds super corny.

It's about the people.

Yeah, it's about hanging out. We just wanna sing karaoke. [Laughs]

I wanted to ask you about your relations to the artists. Are they your friends? How do you know all these people?

I think it's really important to come from a place of friendship and relationship building, because truly, I've learned so much about how much trust is needed to do any of this. It's a lot of coordination. It's a huge honor that the artists trust me to be able to do this. Some of the artists, actually, I had not known at all. I just approached them on a whim and have been just a long time admirer of their work. People like Amy Ching-Yan Lam. I had never met Amy before. I just reached out because I've always been such a fan of her work, ever since she was in this artistic duo called Life of A Craphead, if you know that work. Oh, you should look up that work. Truly, it’s the artists deserve all the flowers.

I've been thinking a lot about what it means to be known and seen. I felt that in this exhibition, there was so much intention in finding the pieces throughout the park and the garden. It was incredibly grounding to come into the space, and be like, okay, let's look for this piece. Not only the work, but the garden itself is so beautiful and interactive. I was really drawn to that. And I wonder if you can speak about that further. Like, what does it mean to be fully seen?

asia jong in 'to carve without cutting' exhibition at sun-yat-sen garden. photography by dax heaven.

I think the nice thing is that you're not always fully seen. And I think that's reflected in – just bringing it back to the idea of borrowing somebody's perspective for a second. Like the way the garden has been designed – you can't fully see it all in one perspective. It takes time for you to seek out or navigate the space in order to fully understand it. And even then, you're constantly faced with new things that you've never seen before. In terms of partnership, I feel like, again, it's that idea of, even for just a second, being able to share an experience, or being able to look and try and understand an experience of somebody else, is really beautiful, but you can never fully understand another person.

That’s a hard pill to swallow.

Totally. And it's just meeting each other where you're at, you know, which I think has a lot to do with the idea of letting the flow of time and the flow of exchange and energy become either in sync and harmonized or to be let go of, which is the case for some of the couples in the show. It’s something that we've all experienced multiple times. It’s important to know when to let that go.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Asia Jong 鍾金玉 is an independent curator, arts facilitator, and writer from Armstrong, B.C., based in Vancouver, on unceded and traditional xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, and səlilwətaɬ territories. She is interested in exploring the contemporary conditions of love and dating, and her practice often centers on collaboration, in particular engaging friendship and relationship building as a framework for art and exhibition making. Recent curatorial projects include exhibitions at: 221A (2024); Duplex Artists Society (2021); Or Gallery (2021); and The Alternator (2021). Her writing has been published by: Capture Photography Festival (2024); Afternoon Projects (2024); Burrard Arts Foundation (2022); Libby Leshgold Gallery (2021); and AsiaArtPacific (2021). From 2019 to 2022 she was a co-organizer of the DIY art collective Ground Floor which supported the work of early-emerging artists.