Moving For Love & Backbone: Brandon Wint’s Exploration of the Body and Jazz

/MOVING FOR LOVE (2024) Dir. Brandon Wint. animation by amelia earheart.

“In my twenties, love was the only word I knew”, confesses filmmaker Brandon Wint in his documentary, Moving For Love (2024). The heartbeat of his work; Vancouver-based filmmaker and poet navigates the complexity of Black identity, the intersections of disability & race, and community-making in Vancouver through the lens of love. His short films, Moving for Love and Backbone (2024) showcased at the VIFF Centre were intimate explorations of vulnerability, creativity, and the ongoing search for connection. The premiere began with musical performances by Black jazz band consisting of Feven Kidane, Yoro Noukoussi, and Quincy Mayes that backtracked Brandon’s spoken word poetry.

For Brandon, it was important to introduce himself before introducing his films. By presenting himself alongside his work, Brandon emphasizes the intimate nature of his storytelling. His films are deeply intertwined with his lived experiences. What sets his films apart is how they engage with the boundary-defying language of music, movement, and poetry – conveying emotion that words alone cannot capture.

In Moving for Love, Brandon delves into the untold story of his family’s migration from the Caribbean to Canada in the early 1970’s. With the guidance of his mother and grandmother, Brandon navigates the emotional terrain of their journey with them, shedding light on the struggle and resilience that fuelled their move to a new life in Canada.

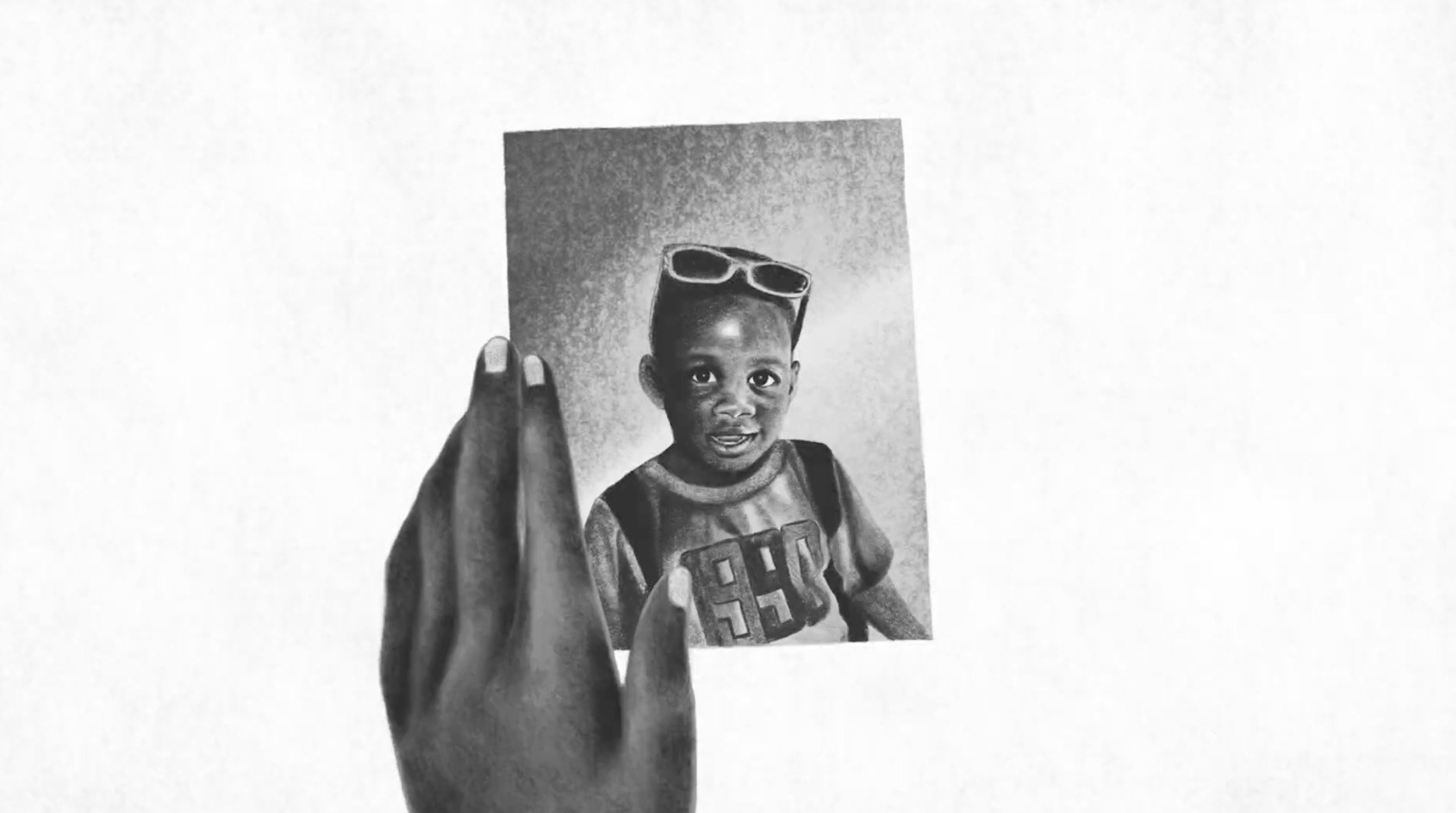

The film opens with a visually striking animation by Amelia Earhart that traces the story of Wint’s family migration. The animation serves as both a historical and emotional portal into the past, grounding in the journey of his childhood. This visual narrative gradually transitions into live-action, where the focus shifts to a dancer, Marisa Gold, her body moving through space with grace and intention. Alongside her, Wint himself emerges on screen, and through a spoken word poem, bridges personal history and poetic expression. The sequence is underscored by the urgent, improvisational rhythms of jazz by Kidane, Noukoussi and Mayes.

Jazz plays a crucial role in defining the tone and thematic resonance of the films. Wint’s use of music is central to the emotional architecture of the films to translate concepts of love and self-identity into sensory experiences. Wint states:

“Jazz to me, more than any other music, communicates with the stars. And so I thought, if I create the sort of films that are propelled by this urgent sonic language, there are things that I will understand through the process of making the film that I wouldn’t have understood, if not for jazz.”

marissa gold in moving for love.

Wint believes that the unique, urgent qualities of jazz—its improvisation, its raw expressiveness— reveal insights and truths that remain hidden otherwise. It’s not just a backdrop for his work. It’s an active force that shapes the way he understands and interacts with the world.

Moving for Love orchestrates a powerful soundtrack that speaks to both the tension and the possibility that Wint sees in Vancouver. Wint acknowledges that the city, while a physical space, also represents an emotional landscape that he is continually re-negotiating. “I have to find ways to make love in this place”, alluding to the ongoing process of reconciling his artistic and personal life with the complexities of a city that is entrenched in colonialism, capitalism, and systemic exclusion: particularly towards those with disabilities.

“Jazz to me, more than any other music, communicates with the stars. And so I thought, if I create the sort of films that are propelled by this urgent sonic language, there are things that I will understand through the process of making the film that I wouldn’t have understood, if not for jazz.”

His words are filled with poignancy: "Every six months, I could write a different Vancouver poem, because my eyes are softening on this city in a way that would produce different words." This acknowledgement of time—of how perception evolves—is a core theme of his work.

Wint’s films are not just about observing the world – they are about participating in it; about opening up to it with a sense of radical honesty.

In Moving for Love, he emphasizes that his aspiration was not just to make a film, but to “interrogate my relationship to life in this city” and to engage more meaningfully with the people around him. His willingness to soften his gaze—to allow for new possibilities—underscores the emotional complexity of his work about being open to the tension between love and difficulty, between connection and isolation.

Drawing on the radical history of jazz as a form of resistance and liberation, Wint sees his films as a way to reclaim and reframe the artistic traditions that have been commodified and watered down over time. Jazz, he points out, was originally a genre born out of struggle and resistance, a sound that sought to tear at the fabric of a colonial and oppressive society. However, in the modern world, jazz has often been relegated to sanitized spaces where its radical potential is dulled for mass consumption.

animation by amelia earhart in Moving for love.

Wint’s films are not just about observing the world – they are about participating in it; about opening up to it with a sense of radical honesty.

In Moving for Love, he emphasizes that his aspiration was not just to make a film, but to “interrogate my relationship to life in this city” and to engage more meaningfully with the people around him. His willingness to soften his gaze—to allow for new possibilities—underscores the emotional complexity of his work about being open to the tension between love and difficulty, between connection and isolation.

“Every six months, I could write a different Vancouver poem, because my eyes are softening on this city in a way that would produce different words.”

Drawing on the radical history of jazz as a form of resistance and liberation, Wint sees his films as a way to reclaim and reframe the artistic traditions that have been commodified and watered down over time. Jazz, he points out, was originally a genre born out of struggle and resistance, a sound that sought to tear at the fabric of a colonial and oppressive society. However, in the modern world, jazz has often been relegated to sanitized spaces where its radical potential is dulled for mass consumption.

Moran Amirah Burns IN BACKBONE.

In his second short film, Backbone, Wint offers a deeply personal exploration of identity and disability, reflecting on his experience with cerebral palsy. The film opens with a visual contrast: Wint walking up stairswith deliberate, measured steps; his body moving through the world with visible effort, each motion reflecting both the weight of his disability and the strength required to overcome it. This is juxtaposed with the fluid movements of dancer Moran Amirah Burns, whose grace and freedom of movement serve as a counterpoint to Wint's own embodied struggle.

In an interview, Wint spoke about the origins of this relationship between dance and disability, recalling his time living in Edmonton, where he often found himself drawn to the local dance scene. "I was like, what is it that I can learn from dancers? Not necessarily more graceful embodiment," he explains. "It’s not that I necessarily wanted to become a dancer, but in the nature of the attention that dancers paid to movement and embodiment, I was like, maybe there are particular lessons for me to learn."

PICTURED ON THE LEFT: WINT WALKING UP STEPS. RIGHT: BURNS DANCING ON THE BEACH IN BACKBONE

This introspection about movement and embodiment laid the groundwork for Backbone. For Wint, dance wasn't about transforming his body into something it was not—it was about exploring what it meant to move through the world as someone with a visible disability, and how movement could become an expression of his lived reality.

film still from backbone.

The integration of dance is crucial in rendering the poetic. Wint sought to translate the tension of his disability—its physicality, its limitations, its effort—into the language of film, using dance as a counterpoint to his own body. "Watching Morgan Amirah on the screen embody this sort of liberated, beautiful, black femininity that felt like an appropriate counterpoint," Wint says. "A lot of my healing in life has to do with healing my relationship to my own feminine energy,"

This integration of dance and vulnerability extends beyond the film itself—it is central to Wint’s broader philosophy of art. In his creative work, vulnerability is not something to be avoided or protected, but rather something to be embraced. "It’s risky to say these things or admit these things," Wint reflects, discussing the act of exposing his vulnerabilities in his films. "But as an artist, I have to be attracted to a certain level of risk in order to grow. I have to permit myself to be scared to take the leap."

The vulnerability Wint practices in Backbone mirrors this broader ethos he holds about art and personal growth: by putting his disability and his body on display, he creates a space for viewers to witness the truth of his experience—unfiltered and raw. And in doing so, he also invites them into a process of collective reflection. “Part of the reason that being a spoken word artist sort of saved my life is because it gave me a way of projecting a little bit of my intentions into the world,” he says. This mirrors his filmmaking philosophy: to hold up a mirror not just to his own experiences, but to the societal structures that shape them.

Through this film, Wint makes a compelling case for vulnerability as a form of strength. "If I’m going to learn from what film is offering me as a mode of expression [it is that] a certain kind of vulnerability is good to practice," he says. "Sharing my art is holding up a mirror to myself."

Both Moving for Love and Backbone are films about reconciling multiple parts of oneself—about love, about identity, and about the transformative power of vulnerability. As Wint continues to push boundaries with his work, he shows us that art, in all its forms, is a vehicle for deep personal exploration. Through his willingness to engage with his own vulnerability, Wint’s films create a space for viewers to reflect on their own vulnerabilities. For him, the very act of creating is an ongoing process of self-discovery, one that offers both personal liberation and, ultimately, a path toward collective healing.

Tasheal Gill (she/her) is a filmmaker and producer dedicated to uplifting marginalized voices, and telling stories through a socially conscious lens. Follow her on Instagram (@tashealll).