Video Evidence of a First Love by Hailey Rollheiser

/Trigger Warning: violence, paragraph 8

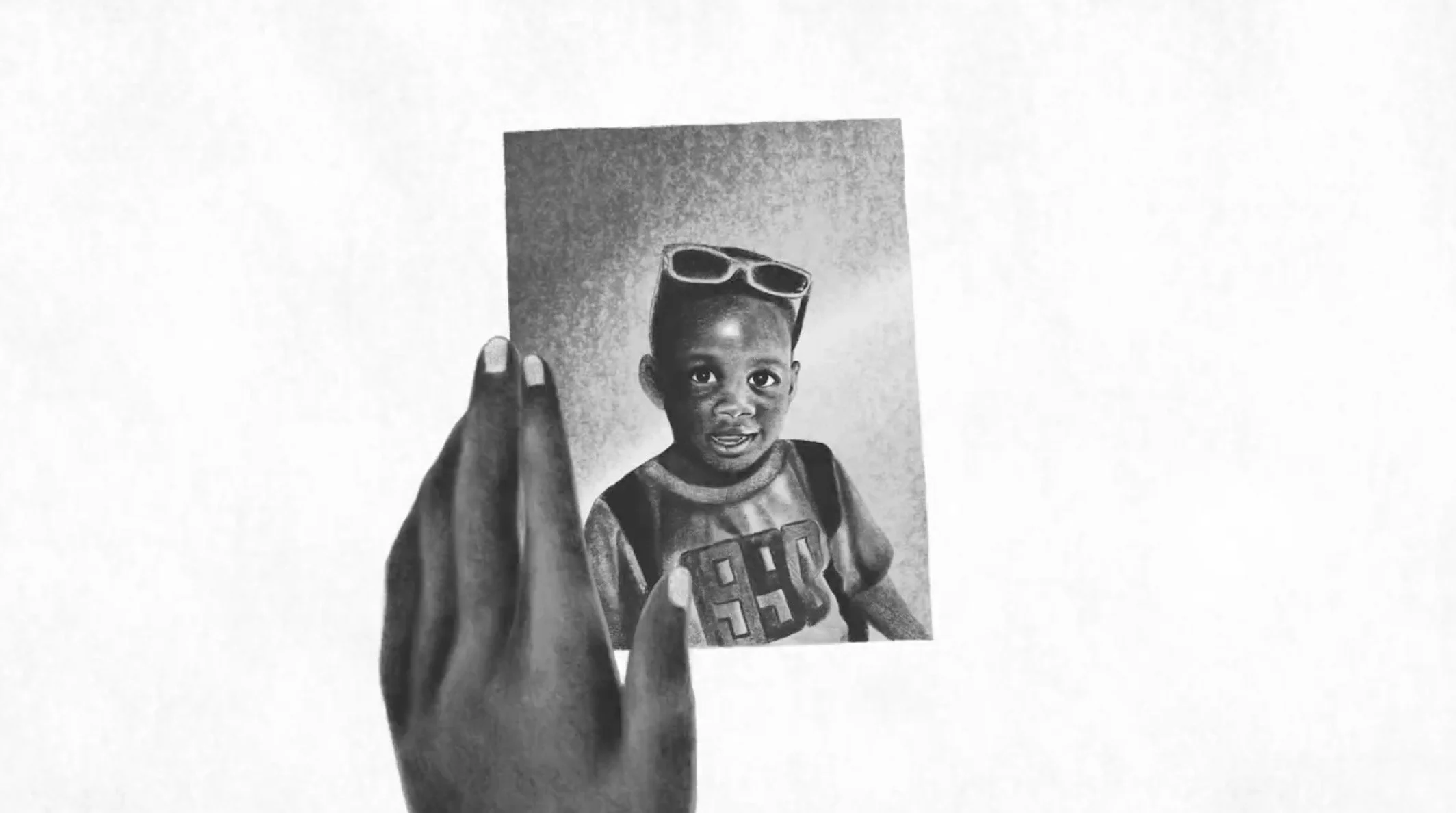

Illustration by: Bronwyn Schuster

Flipping through my old Blackberry photos from 2011, the one from high school, I found photos of at-home dye jobs that left the blondes—myself included—brassy, the brunettes closer to red. I smiled at how young we looked, frolicking in the freedom from ourselves that we found in plastic bottles of Smirnoff vodka. With alcohol we acted older than we were, escaping our teenage selves and emerging fearless. Later, we hid behind it: I didn’t mean it, I was just drunk. Our eyeshadow unblended, our foundation a tone off our skin colour, our crop tops and skirts hardly covering our bodies. We were gloriously unburdened.

My blackberry was also full of photos of my first love. I thought I’d deleted all traces of him, but snippets of evidence remained. He looked baby-faced; his fair skin smooth. His dark blonde hair was short then. His lips were soft and full; I could almost remember what they felt like. His big blue eyes were looking at me behind the camera, smiling his mischievous smirk. That look in his eyes that always reeled me in; proof that once, we were happy together. Like many couples, I had become well-versed in reading his facial expressions from across the room at a crowded house party at someone’s parents’ house, or down the hallway at school in between classes, or in bed, when we’d lie together and I’d trace his features with my fingers, repeatedly, memorizing his face. A decade later, I can still feel when his eyes are on me when we’re in the same room. I can still read his facial expressions, but maybe he would disagree.

We were only seventeen. We fought relentlessly. If an objective third party wrote a list of every time one of us hurt the other, along with all the toxic behavior we engaged in, would they call it love? Maybe not. But the objective third-party would never know the way he made me feel. I had idealized our relationship, forgetting our arguments, and his cheating, in favor of replaying the romantic memories in my mind—how we sang “Happy Together” in the car, how we exchanged promise rings for our one-year anniversary.

When I exhausted the photo album, I opened the videos. It was there I found a video, recorded on my phone at 1:50 am, in his bedroom. I pressed play and at the first sound of the muffled voices, I felt like an intruder, like I was eavesdropping on a couple arguing at a party, after stumbling into the wrong part of the house. The phone was in my hand; the view was dark. We were both drunk. I was angry with him for what seemed to be no real reason. I had a habit of becoming resentful over something minor–if he didn’t text me back quickly enough or meet me at my locker between classes. I’d keep it to myself until I drank and then it would resurface as unrestrained anger.

“You don’t love me.” I winced at the sound of my own voice, antagonistic and detached. I was miserable, trying to pull him into my pain, insisting that he suffer with me. I was shocked at my own coldness, the way I was pushing him away, provoking him to leave me. He only offered declarations of love, but I was insecure and jealous; I was testing him. I wanted to break him.

I wanted to reach through the screen and shake my drunk seventeen-year-old self. I wanted to crawl into bed and wrap my arms around him. But I couldn’t, I was just a powerless observer to this past suffering, this nine-year-old argument. The role of the merciless antagonist was one that we had taken turns trying on throughout our relationship. We pushed each other away to see how hard the other would fight to run back. But to see myself in this role, so irredeemably villainous, was horrifying. I felt nauseated with shame. The nature of my own memory tends to gloss over moments like this, preferring to remember myself as the near-perfect victim. Yes, I had made mistakes but only when backed into a corner—the instinct to occupy the space of hero and victim simultaneously.

In my hand, the dark, obscured view of the camera is dreamlike—mostly pointing down at the floor, sometimes flashing up for a quick glimpse of him lying in bed, and then back down at the plush white carpet. It reminded me of all of the fragmented dreams I had about being in his house, his old bedroom. Watching the video was like being in a dream—all emotion and no logic. I was a powerless observer witnessing an eerie window into the past, yet I was unable to change it.

He got up and left the bedroom. There were a few moments of silence before I followed him to the kitchen. The image is unclear but I could hear my voice, panicked, asking him what he was doing. He punched the wall. His knuckles were bloodied. I remembered believing that it was my fault. I embraced him and the camera faced down, at our feet, my toes on top of his as I got as close to him as I could. I was broken out of my reverie, and we spoke in an absurdly sweet tone to each other. Just like that, my needless cruelty was finished, and the video ended on this cinematic note. I felt as though I had witnessed a performance of sustained apathy until I finally collapsed into a warm, empathetic kind of love, at the sight of his blood.

It is here when I really see us: two seventeen year olds trying their best to navigate first love, to manage the emotions that screamed inside until they were let out. The unbridled pain that existed plainly between us. Our arms around each other after–strengthening our bond after trauma, reinforcing the cycle of toxicity. I wanted to tell my seventeen year old self that love doesn’t need to hurt.

I am not my younger self—she was bold, brash, reactive. She lunged at the opportunity to speak her mind, her confidence lent by immaturity, a misplaced self-righteousness. But maybe in some ways, I am still the same. I still push people to their limits, push them away, hurt them before they hurt me. I’ve yet to experience another love as intense as ours, but I have hope that someday I will. It’s possible that I will always love him, for the role he played in my life, and I’m starting to see more of the beauty in that and less of the pain. I’m learning to hold both at the same time.

I put my old Blackberry away, in a new spot this time: in the box with my old promise ring, and old love letters. I didn’t delete the video. I don’t intend to watch it again but I kept it as evidence, tangible proof, that once there was this incredible emotion between me and another person. I was flawed, but I was loved. This is an apology, an offering, to not only him, but myself too. Forgiveness, like love, is a gift.

Hailey Rollheiser is a writer in Vancouver, B.C. She completed a B.A. in English literature at the University of British Columbia in 2017. Her work has appeared in Hobart, the Rumpus, and Loose Lips Magazine. She is a graduate of The Writer’s Studio at Simon Fraser University. You can find her on Twitter.