I Am Because They Were: A Review of Berlynn Beam and Chase Keetley's We Lost People: Diasporic Departures

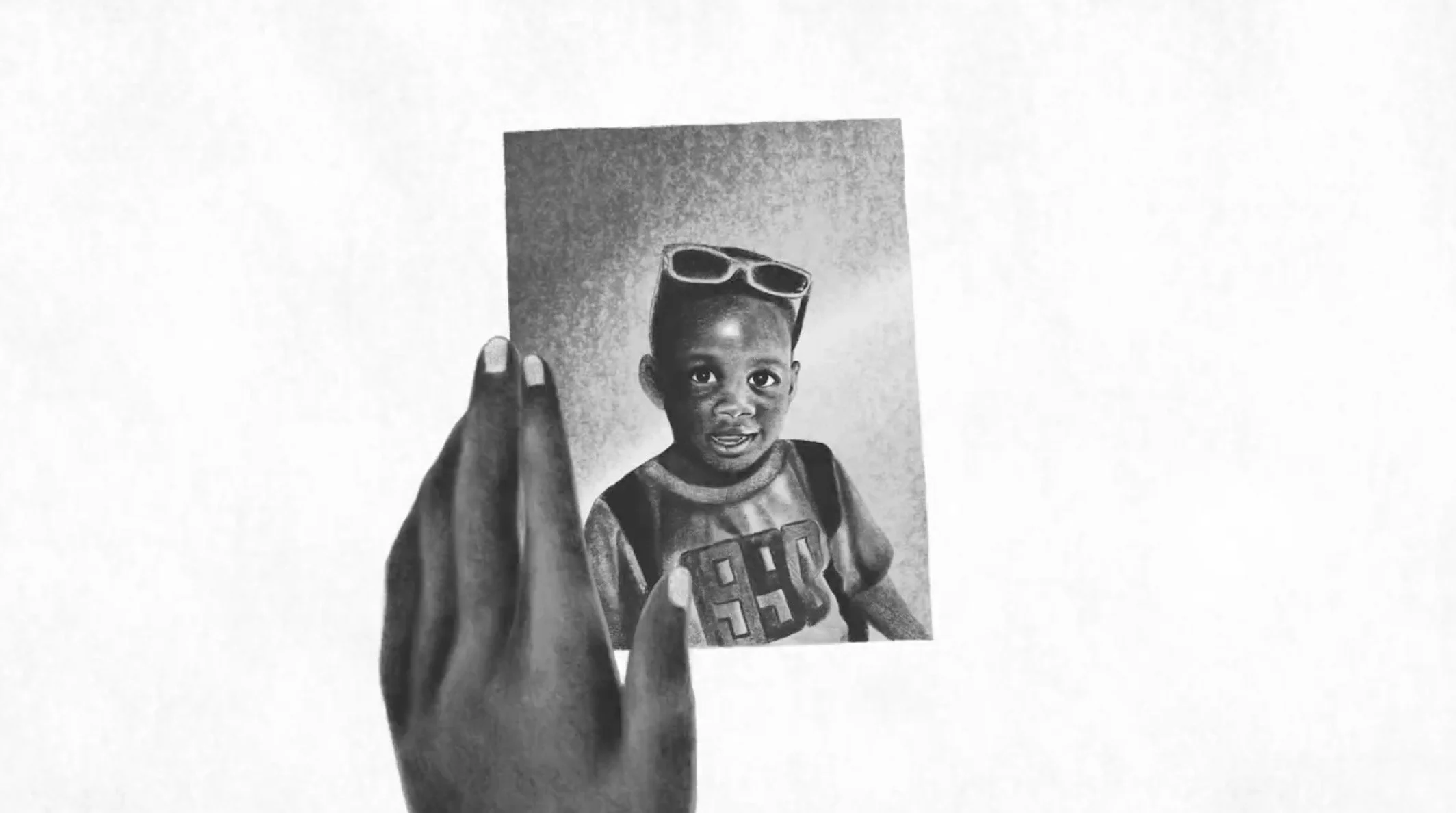

/Photo courtesy of Sarah Race

Throughout the past two years of civil unrest, financial collapse, and pandemic, we have each been reminded of the frailty of both our systems and our bodies. Whether this frailty struck us in the form of lost loved ones and Zoom-sponsored funerals, or through government-sanctioned murder turned viral video, it has become undeniably clear that radical systemic change is needed to address the continued subjugation of the displaced and disenfranchised. For those who, thanks to the sacrifices of those that came before, march for a post-colonial future either in spirit or in the streets, survival has also reminded us to breathe, to grieve, and to remember. In the same light, We Lost People: Diasporic Departures by Berlynn Beam and Chase Keetley of Black Arts Vancouver – on view at UBC’s Museum of Anthropology as a part of Sankofa: African Routes, Canadian Roots – invites viewers to pause and consider the land we gather on, the places we come from, and the people we have lost.

At first glance, We Lost People: Diasporic Departures is conceptually intimidating. The multimedia installation lies in an all-white room near the back entrance of Sankofa and is juxtaposed by two phrases written boldly across the walls as part of Millennial Proverb – a vinyl installation by Nya Lewis Williams. The phrases read “WE ARE THE ONES WE’VE BEEN WAITING FOR” and “I AM BECAUSE THEY WERE BECAUSE YOU ARE”. Although from a different installation, the carefully placed words are in direct conversation with We Lost People: Diasporic Departures and provide a lens through which onlookers can see themselves as future ancestors and as modern revolutionaries.

Beam and Keetley’s diasporic tour de force features an imposing, suspended stone altar, topped with offerings for those lost this past year and ceramics that hold materials traditionally used in ritual burning practices. Beneath the suspended altar lies another stone structure that is similarly topped with offerings and is surrounded by dirt collected at Hogan’s Alley – a historic Black community in Vancouver, on the traditional territories of the Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, and Musqueam peoples.

Further, We Lost People: Diasporic Departures makes use of Adinkra symbols, specifically Mako, Nkyinkyim, and Nkisi Sarabanda–each with their own significance to the installation and to traditional West and Central African teachings. Mako, representing uneven ground, is the symbol depicted by the earth surrounding the altar; while the teachings of Nkyinkyim – referring to the dynamism of life’s course – and Nkisi Sarabanda – symbolizing the metaphysical connection between the spiritual world and the world of physical existence – inform the work as a whole.

Photo courtesy of Sarah Race

Photo courtesy of Sarah Race

The installation is as much a powerful portrayal of the undying nature of African epistemologies and the African diaspora, as it is a solemn reminder of loss of life due to pandemic and violence, and loss of place in the cities we call home and in the histories we are taught. As such, the conceptual complexity of We Lost People: Diasporic Departures is predicated upon its marriage of present circumstances and West African metaphysical approaches, which cement the installation’s underlying conversation concerning the continual erosion, rebuilding, and redefining of Black cultures.

The only reasonable critique of We Lost People: Diasporic Departures lies in its greatest strength. That is to say, the same conceptual diversity that lends the installation its overwhelming significance and meaning necessitates a deep-seeded understanding of African peoples, the diaspora, and the spirituality that informed our Ancestors – something colonialism took from many of us. The work, on one hand, can make viewers feel connected to a wider diasporic community, spanning across enough breadth to hold all the beauty and grief in the world; while on the other, it can make the continent and its teachings feel foreign and far away. In a place like Vancouver, where we make up a sliver of the population, on land we did not mean to settle on but had to, my people, our peoples, the reason I am and the reason we collectively are, can all be made to feel distant. However, this does not take anything away from the importance of We Lost People: Diasporic Departures. The work challenges the viewer, specifically the Black viewer, to remember themselves, to search for their place in our collective existence, and to seek the past in pursuit of the knowledge either hidden from us by Western Aryanism and mass displacement or concealed under too many layers of trauma to peel away alone. It is this very challenge that makes We Lost People: Diasporic Departures a perfect fit and a standout piece of Sankofa: African Routes, Canadian Roots.

In all, We Lost People: Diasporic Departures is daunting, transformative, and grief-inducing all at the same time. By way of its conceptual and cultural hybridity, the installation provides two intersecting lenses through which viewers can interpret the installation’s significance and meaning. The first, We Lost People, gives viewers the space to mourn those who have recently left us, and to consider the things that bind us – the tragedy we each own, the colonialism we witness, the blood and loss that brought us here, and the bittersweet triumph of survival in the wake of carnage. In the hands of Beam and Keetley, the suspended altar signifies a resting spot for those lost and a space for Black people to gather. It also stands in place of the true stability colonialism plundered from the wretched of the earth. The second, Diasporic Departures, reminds Black viewers that it is up to them to recontextualize their cultures after mass displacement and exodus. Insofar as continual migration, necessitated by the natural movement of humans, genocide, slavery, or colonialism, is a way of life for Black people, insofar as the preservation of our cultures rest on our shoulders, the displaced are called to seek the past, to remember what was and to create spaces for cultural reimagination beyond the Master’s house. With these things in mind, We Lost People: Diasporic Departures asks us not only to grieve, but also to celebrate the beauty and horror of our own displacement – we are the fruit of our ancestors’ survival.

N. Lema Lubendo is an emerging African-Canadian poet, essayist, and art critic based in Vancouver, British Columbia. As a child of Congolese refugees and a student of revolutionary movements, Lubendo’s writing largely focuses on post-colonial theory, urban poverty and the conditions it engenders, and the history of both his family and people. He appears in the anthology, Cotyledon (Vancouver Poetry House, 2021), in Maple Tree Literary Supplement's 25th issue (2022), and has been featured in No Ducks (2021) – a publication by Mount Allison University's Owens Art Gallery. Follow him on Instagram for more (@n.lemalubendo, @noahlubendo).