BARE ESSENTIALS: The birth of a photography career

/10 YEARS OF TEARS

It's our 10th anniversary this year and we're feeling a little weepy‒that’s why we’ve dusted off the archives to bring you highlights from our back issues over the last 10 years. Join us as we take a look back at 10 years of SAD Magazine, revisiting the memories and the people that made SAD what it is today. We're not crying, you’re crying.

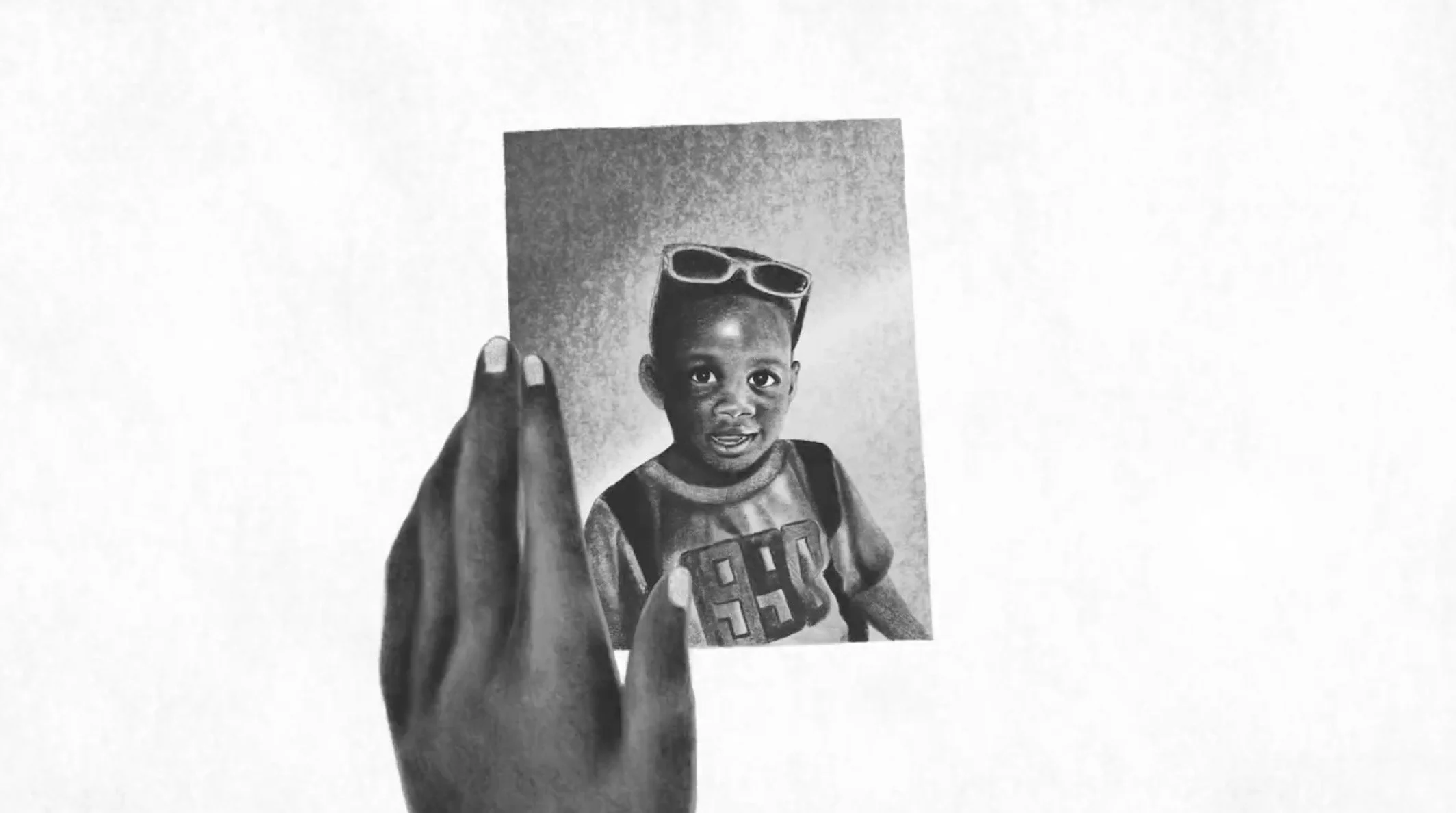

Photography By: Jackie Dives

Jackie Dives is a Vancouver-based doula and birth photographer who received widespread media attention in late 2013—from Daily Mail, Huffington Post, My Modern Metropolis, and more— in response to a series of photos captured while attending home births. We met in her kitchen, an appropriate setting to discuss her new photo series, where she captures portraits of people eating comfort food in the nude. A collection of film and digital cameras were arranged like a makeshift centrepiece, and a large unfinished canvas was set in the corner. We drank root beer and discussed nudes, comfort food, and birth culture.

Hannah Bellamy: What is the most unexpected experience you’ve had in your adult life or career?

Jackie Dives: Two things come to mind, and they are not necessarily solid events. One is that it took me awhile. I graduated from high school in 2002 and it wasn’t until now that I felt like I had discovered what I should be doing. I’ve always wanted to take pictures, I’ve known that from the beginning. And I’ve always wanted to work with people in need. Doulas aren’t necessarily working with people in need, but we are working with vulnerable people and offering support during a vulnerable time. It was unexpected that my love for photography and my desire to work with people in a caring profession would come together and create the perfect job for myself.

The second thing is, despite going the long way around, because I haven’t gone to school for either jobs, I still ended up doing something that I can make a living at and that I’m proud of. That’s unexpected to me because I would have said two or three years ago that I had no expectation to find a career that’s worked as well as it’s working.

HB: What has been your favourite project?

JD: I did a cool project over the past year and a half. I wanted to learn how to paint, and I wanted to paint big, for some reason. I couldn’t afford to buy the canvases because the ones I wanted to work on were that size (gestures to a canvas in the kitchen)—pretty big, made of wood, and like 80 bucks. I had gotten a show based on my mixed media work a few months in advance at a cafe and I didn’t want to do that work anymore. I felt [I was] past the mixed media stuff and I wanted to learn how to paint.

So I put on Facebook, “If you want to support a local artist, I’ve got an idea for you.” I told them they could pay me 85 bucks and I would paint on a canvas that I purchased with it. If the painting sold in the show, they would get the $85 back. If the painting didn’t sell, they would get to keep the painting. Surprisingly, I had more than five—I was going for five— people say they would do this, even though all of them knew I’d never painted before. It was cool to learn that people wanted to support artists. In addition, people liked the paintings and I ended up selling a few.

HB: Where did your interest in women and birth come from?

JD: It’s hard for me to point to exactly where it came from, but ultimately it came from my self-exploration of being a woman. Even when I was a teenager, my bookcase was full of self help books for women. I always liked coming-of-age stories, women’s health, and I was really curious about what was going on with me. I think that people don’t really talk about puberty and menopause and other things that are difficult.

My interest was a progression. I became interested in do-it yourself culture and holistic and naturopathic stuff. Using herbs, using medicines from the earth, using your intuition, and trusting your body to do what it needs to do. I started reading novels about birth and midwives. I had pondered being a midwife, but that didn’t seem to be the right option for me.

And then I met a doula. That was it. I knew that’s where I belonged. A lot of doulas say as soon as they attend their first birth, or as soon as they meet a doula, they know. I completely agree; the first birth I went to was one of the greatest experiences of my life. I cannot imagine living my life without going to births. It’s so magical.

HB: Where does being a doula and being a photographer intersect for you? Is it mostly an intersection of your personal interests, or do you see some other connection?

JD: It just started with me having my camera with me all the time, and because of that, I would take photos while I was at births being a doula—with permission, of course, always. But then I realized that I was doing something that was powerful and special. Capturing the first moments of a life is amazing. It’s cool as a gift to the family, and I find it incredibly fulfilling.

But as my images became more widely viewed, I realized these images I was taking and posting online were making a difference. I was changing birth culture, and changing it in a positive way. For me that was the ultimate desire. As a doula, you want to impart this feeling on women that they can do whatever they want, including giving birth. They can trust their bodies. Photographing these moments, when women are doing that, is sort of photographic evidence that women can do what they want. It’s not someone telling them they can; it’s showing them they can.

I think there is a lot about birth that’s going on right now that is really unfortunate. The power has been taken out of the woman’s hands, and it needs to be put back. Women can birth their babies without the help of anybody else. These images being posted online and then going viral mean that lots of women have seen them. I’ve been receiving emails from women all over the world saying because they saw my photos, they aren’t afraid anymore. To hear that is maybe the most amazing thing.

HB: I hadn’t made the connection that birth photography could change birth culture.

JD: I’ve always wanted to take documentary-style photos. I feel like I’m always shooting from the hip, wanting to capture motion and not wanting to be a big presence in the room. In birth, that’s it. There’s no other option because a woman is not going to pose for the camera. She’s just going to do what she needs to do, and I get to capture it. It fills the need for me to be a documentary-style photographer.

HB: How does Vancouver as an aesthetic place influence your work, which focuses on people, and mothers in particular?

JD: Usually when a client wants me to do their maternity photos I ask them: where is somewhere you would like to be in the photos? Often it’s somewhere in Vancouver and close to their home. I want them to look back on these maternity photos in 10 years and say, “Remember when we lived there and had our maternity photos done?” And I want them to be able to see the landscape in the background so it’s not just a photo of a belly, but it’s a photo of where they were in that moment in time.

Vancouver is so beautiful that it makes for an awesome backdrop. There are so many places to choose from, and I’ve almost never overlapped. I think I’ve shot Jericho Beach twice, but usually I go somewhere new even though I’m leaving it in the hands of the client. As I get better and better, I find that I’m including more of the scene. I’m stepping farther and farther from the belly and including the environment. I don’t know what that means.

HB: Well, some of the shoots seem to have a story to them, like the one with the couple that took a Modo car to the hospital.

JD: Most of my photo shoots feel that way. I get that a lot. People say it’s narrative, or they can see there’s a story being told. It might have to do with the fact that I include the environment in the shoots. I don’t know if that’s different than anyone else in maternity photography, but I definitely find Vancouver inspiring, especially in the woodsy areas. The more off the path I can go, the happier I am. In the last maternity photo shoot I did we went to Capilano Canyon and we trekked into the forest. There was no one around and you couldn’t see any paths and we stuck her in the trees.

HB: How does your new series “Comfort Food” compare to your past projects?

JD: I stumbled upon a similarity between all my projects without even realizing. Someone else pointed it out to me. I usually work with vulnerabilities. Generally there is some sort of vulnerable aspect to what I’m doing, whether it’s birth photography or photos of people naked eating their comfort food. I also do bereavement photography for parents who have lost a baby. That’s a hugely vulnerable situation. When I was listing these things off to someone, they were like, “you seem to work in emotionally charged situations.” I think that would be the thing that draws me. I love some sort of vulnerability or charged emotion.

HB: Did another project inspire “Comfort Food” in terms of vulnerabilities or emotion?

JD: No, where it came from was thinking about two things that I wanted to take more photos of. One of them was nudes. I like taking nudes. I think they are interesting. Most of the time, they are more interesting than clothed photos. The other thing was something that was textured and colourful. That was probably the beginning of the idea. I find myself eating food a lot to comfort myself, that’s one of my issues that I struggle with. Being naked in front of people is another issue that I struggle with. Those two things together were like a powerhouse of struggling and vulnerability.

HB: Why is nudity significant in your projects?

JD: Nudity makes people more vulnerable. I think you get a more interesting facial expression on someone when they’re not wearing clothes. They’re feeling different things. Also, naked bodies are interesting. They’re just cool. All of them. All sizes. I think ultimately it just creates more tension, which is perhaps what I’m drawn to.

HB: Do you do anything different technically or aesthetically in a nude shoot?

JD: The naked dynamic makes it much harder because you have a finite amount of time for them to be okay with their photo being taken. I find they become less comfortable as time passes. After 10 minutes of shooting it’s like they have reached a threshold and they don’t want to be naked anymore. That’s the point when it’s difficult as a photographer because you probably don’t have your shot in five or 10 minutes.

It’s a balancing act of going for it and getting the shot as quick as I can while not worrying about things I might worry about in another kind of shoot and stretching it out as long as I can.

HB: How do you approach nudity in your photography?

JD: It’s easy in the birthing situation. Women are doing whatever they want to do in the photos. Normally a woman wants all her clothes off when she is about to birth her baby. I’m cool with that. I’ve seen, like, a hundred vaginas.

In terms of getting people who are my friends or acquaintances to take their clothes off and be comfortable in front of the camera, usually the first step is to ask them to do it. I think for some people, doing it is like a personal challenge. They’ve said yes because it’s going to be difficult and they want to do it anyway.

My opinion about making people feel comfortable when I’m behind the camera and they are naked in front of it is pretending that they have clothes on. I don’t treat them any differently than I would if they were wearing clothes. I look them in the eyes, get close to them, maybe rearrange their hair, or put a pillow behind their back. I do whatever I need and I’m not afraid of seeing something I don’t want to see or saying something I don’t want to say.

This piece was first published in 2014 for Issue No. 15: Grit & Gristle.

Visit our shop to purchase this and other past issues of SAD!