VIFF 2018: ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch

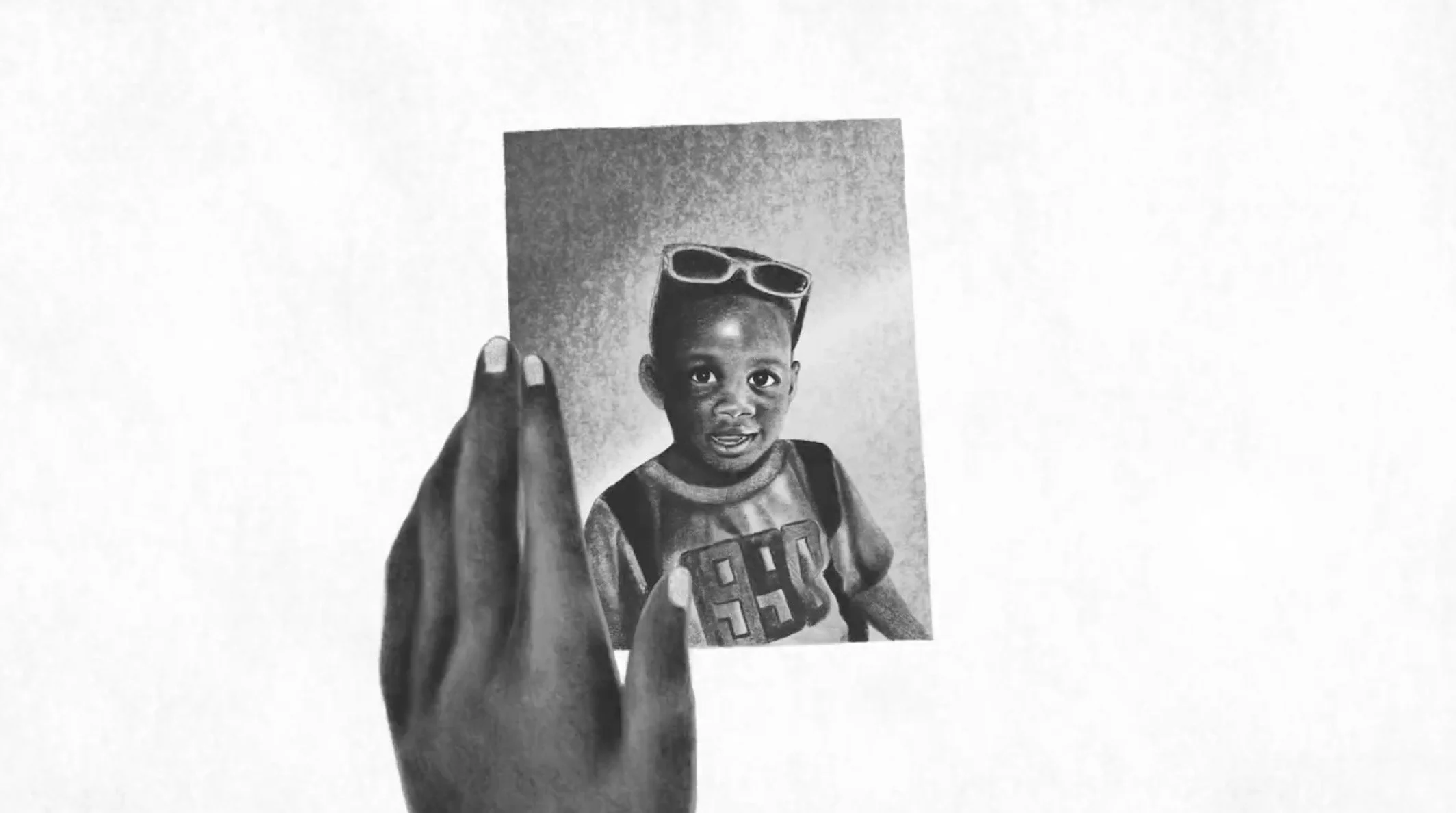

/ANTHROPOCENE film still via Vancouver International Film Festival

The first shot of ANTHROPOCENE: the Human Epoch takes place in the mouth of a fire. The flames are beautiful and deafening. When the shot pulls back and the source of the blaze is revealed to be a massive pyre of elephant tusks, I feel a mixture of awe and unease. This sensation visits me regularly throughout the film. ANTHROPOCENE’s directors—documentarians Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, and photographer Edward Burtynsky—have experience dealing in these contradictory feelings. Baichwal and Burtynsky successfully executed this visual paradox in the 2007 documentary Manufactured Landscapes, and ANTHROPOCENE re-purposes it to support its claim: that we have left the Holocene Epoch and entered the Anthropocene. This epoch is unique, as it marks the first time in earth’s history that humans impact the natural world more than all natural systems combined. We are all implicated, the filmmakers insist, and we have to change our behaviour now to avoid damaging our world irreparably.

ANTHROPOCENE makes its case through a predominantly visual language. In each of the film’s seven sections the voiceover volunteers a definition and statistic, then steps back to allow the surreal landscapes to speak for themselves. We are told that humans move more sediment annually than all the rivers of the world, and are transported to the marble mountains of Carrara, Italy. The camera pulls back from the swirling stone to reveal the rusted metal mouths of machines, upending themselves in attempts to rip off chunks of marble. We are told that humans dominate more than 75% of the land on the planet that is not ice, and the film cuts to the Hamber Coal Mine in Germany where a machine resembling a mechanical ferris wheel burrows into the earth.

Vancouver Island’s old-growth forests appear in the film, shrouded in fog and drastically denuded. The voiceover bemoans that only 10% of old-growth forests remain on Vancouver Island. For the first time during the film I notice that people around me are shifting and mumbling, visibly uncomfortable. A man, holding a baby, gets up and leaves the theatre.

ANTHROPOCENE doesn’t feel explicitly accusatory. Instead, the film suggests that the culprit is the industrial practises that have formed over the last century, and the disregard they have for the people they displace and the resources they devastate. We all participate in these practises at some level along the commodity chain, whether we are extracting, manufacturing, or purchasing the spoils of industry.

The horrors of ANTHROPOCENE are very real, but so are the glimmers of hope. We are, as the filmmakers insist, all implicated, but we are also capable of enacting positive change. The film deftly cuts from moments of extreme despair to promise. We see a converted World War II bunker underneath London, England, housing plant beds in lieu of bunk beds. Animals that are “functionally extinct” are alive, but in captivity. Ultimately, ANTHROPOCENE reminds us that anything made by humans can be dismantled by humans, and asks us what we are going to do about it.

ANTHROPOCENE: The Human Epoch has no more screenings in VIFF, but you can learn more about the film at theanthropocene.org.