Hazel Isle: An Interview with Jessica Johnson

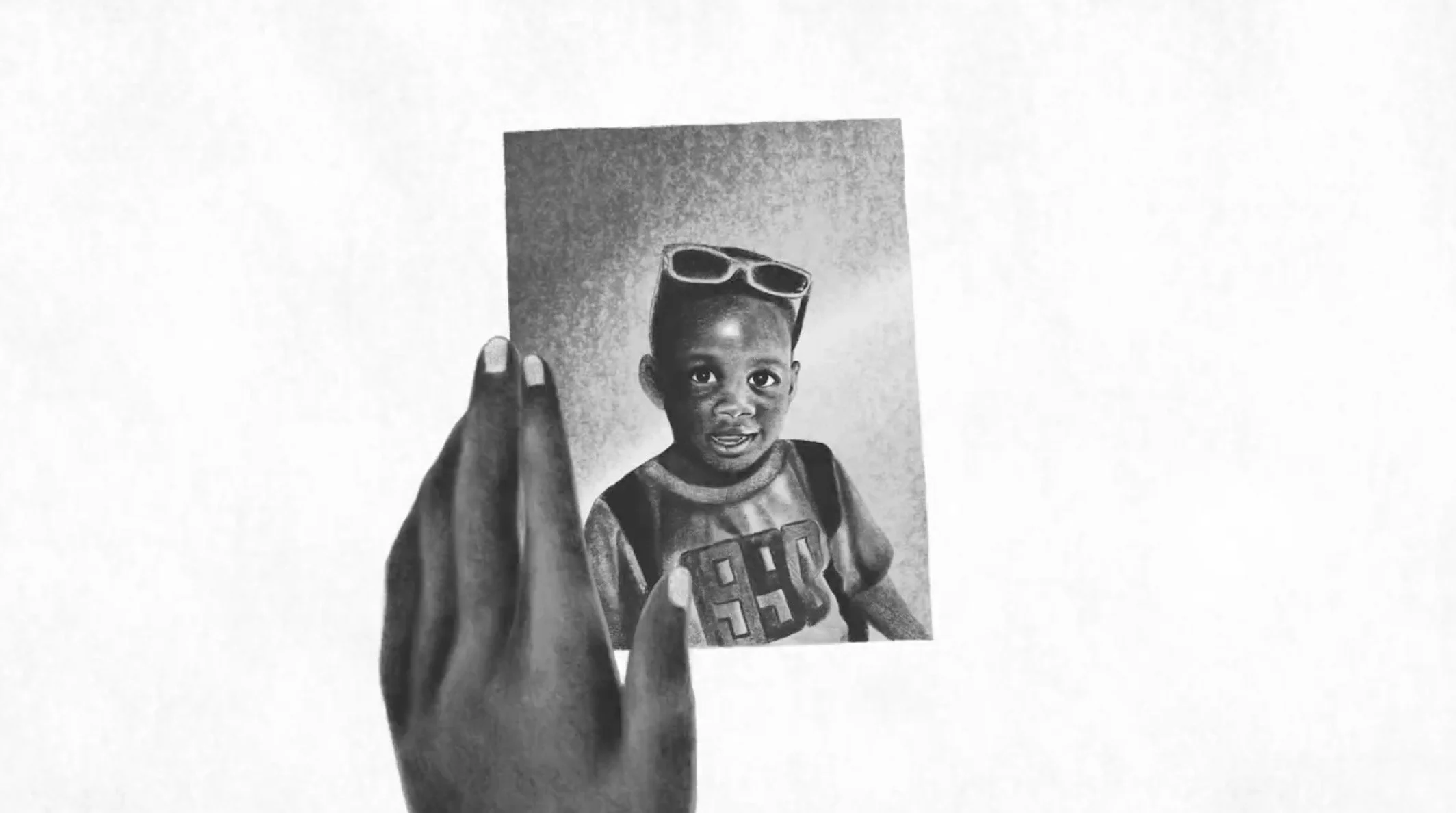

/Film Still from Hazel Isle.

To prepare for my interview with independent filmmaker Jessica Johnson about her newest experimental short documentary Hazel Isle, I did a cursory web search on the film’s namesake: the Scottish Isle of Coll. I jotted down facts. It is home to rare birds (corncrakes) and bugs (short necked-oil beetles). It has Dark Sky status. The island’s small circumference is dotted with shipwrecks. When I asked Johnson about how she prepared for the film, I was surprised to hear that she went in with less information than I had gathered in those hasty fifteen minutes.

“I wanted to go there without knowing anything,” Johnson explained, “I wanted to discover it on the ground rather than through literature, and embody a diaristic style of filmmaking by literally showing up with my camera.” Inspired by filmmakers like the avant-garde Lithuanian-American Jonas Mekas and Scottish documentarian Margaret Tait, she aimed to follow a simple process. She would film the things she came across each day, using the camera to mediate her travels around the island. The process of reflection came during editing, as Johnson parsed through the narration of locals who showed her around the island and paired their voices with images after the fact. This formula makes the film feel like a series of memories you carry home from a trip; contemplative shots of ruins, the roar of wind, and the stories of locals are all enmeshed and in no particular order.

Jessica Johnson. Photo by Victoria McGhee.

This methodology is motivated by more than form. Johnson saw this process as a way of exploring her family’s history on the Isle of Coll. She recounts, “I was interested in making a film about a history that isn’t recorded. I was influenced by the fact that my heritage that’s from [the Isle of Coll] is one that’s impoverished, so no one from my family has a marked grave. There’s no history in writing of my family, really, other than the census they were part of when they moved from Coll to Canada.” By filming the place her family occupied for centuries but has no documented ties to, Johnson used 16mm film to glean meaning from a seemingly neutral landscape. Using long takes of the scenery, she invites the viewer “to look at ruins, or places that you maybe wouldn’t suspect had anything under the surface of the grass.”

The weight of time sits heavy on the Isle of Coll. There are ruins dating back to the bronze age. Skeletons of stone houses lilt on quaint hilltops. A local told Johnson that a German submarine from World War II sleeps deep off the coastline. This significance of these relics are not lost on Johnson—her interest in filmmaking is twinned with her background in archeology. “In university I took a landscape archeology class,” she explains, “I got really into the idea of witnessing what landscape can tell us about human history, and how people have utilized, abused, or taken the land they live on for granted.” Her previous films, made in collaboration with experimental filmmaker Ryan Ermacora, explore this idea around British Columbia: their film E & N muses on the implications of Indigenous land rights by documenting the unfinished Esquimalt and Nanaimo Railway on Vancouver Island; Ocean Falls studies the remnants of industry and human habitation that a pulp mill left behind.

Film still from Hazel Isle.

As in her past films, Johnson lets local’s narration dominate the soundscape of Hazel Isle. She got in touch with her guides through a Facebook group called “Descendants of Duncan Johnson.” The group, which connects 115 people who descend from one man on the Isle of Coll, led her to a man named Robert McGhee who she is “potentially related to 200 years ago.” Robert gave Johnson a place to stay, helped her around the island, and introduced her to a Gaelic teacher named Kirsty whose voice figures predominantly in the film. Kirsty’s musings on the loss of the Gaelic language, and the struggles between local Gaelic-speakers and wealthy English-speaking newcomers, give context to the hulking ancient stones peppering the vista’s of Coll.

The final shots of Hazel Isle, paired with the stirring vocals of Gaelic singer Callum Kennedy, see the Isle of Coll fading into the distance shrouded in clouds. I watched these shots in awe knowing I was witnessing something ancient, something that humans had been regarding for thousands of years.

-----

Hazel Isle has its world premiere in the Various Positions program at Vancouver International Film Festival this month. Catch the film at International Village on October 3rd and 10th. Showtimes and tickets can be found here.