In Conversation with Suzette Amaya

/Let Them Build a Bighouse

The sun sets pink behind her as Suzette Amaya smiles warmly into a camera,“Gila’kasla.” Using a different tone than her usual “Hey everybody!” pep, reserved for her speaking engagements and reality TV persona, Suzette is filming a promo for the radio show she hosts and produces on Co-op Radio 100.5, ThinkNDN. A member of the Kwakwak wakw, Cree, Nisga, and Coast Salish nations, Suzette has transitioned to a bona fide media personality over the course of her two-decade career in the public eye. In a few days, she heads to Toronto with the Indspire tour, an Indigenous-led charity supporting Indigenous education.

“I’ve been touring straight, since 2007.” She sighs, but her voice is still energetic. “Every year. When I’m home, I work graveyard shifts at the Women & Children’s Shelter. Sometimes doubles.” When does she sleep? She pauses. “Uh, well I never sleep.”

The Indspire tour, this year sponsored by Canada 150, makes a stop each month to select cities where the sponsored laureates take part in panel discussions about the lives of Indigenous youth across the country and how education makes for a brighter future.

But for Suzette, as for many Indigenous people across the country, Canada 150 is a sticking point. To many across Canada, the hundred and fiftieth anniversary isn’t cause for a celebration. Instead it feels like a glorification of colonialism, and continues to downplay the injustices that Indigenous people have suffered at the hands of the colonizers.

And Suzette agrees. “It’s almost as if they’re saying “Look at us, we built this great country. But they’re not saying the truth of how they built this country.”

She spent her early childhood in East Vancouver and moved to the Tsulquate Reserve near Port Hardy as an early teen. “For me, it was coming off reserves to the “big city” of Vancouver. I felt a need to build a community and I didn’t know what it was like to be Indigenous person in mainstream society.” Fuelled by the injustices suffered by herself and others in her community, Suzette studied anthropology and criminology at Douglas College and even applied to be an RCMP officer.

In 2007, she was appointed a Role Model for the National Aboriginal Health Organization. Role models are nominated by their peers and selected for their “achievements, leadership and innovation”. It was her first time touring across the country, attending schools and conferences to speak to Aboriginal youth about Aboriginal identity, self-esteem, healthy lifestyles, and to encourage Aboriginal leadership within their communities and beyond.

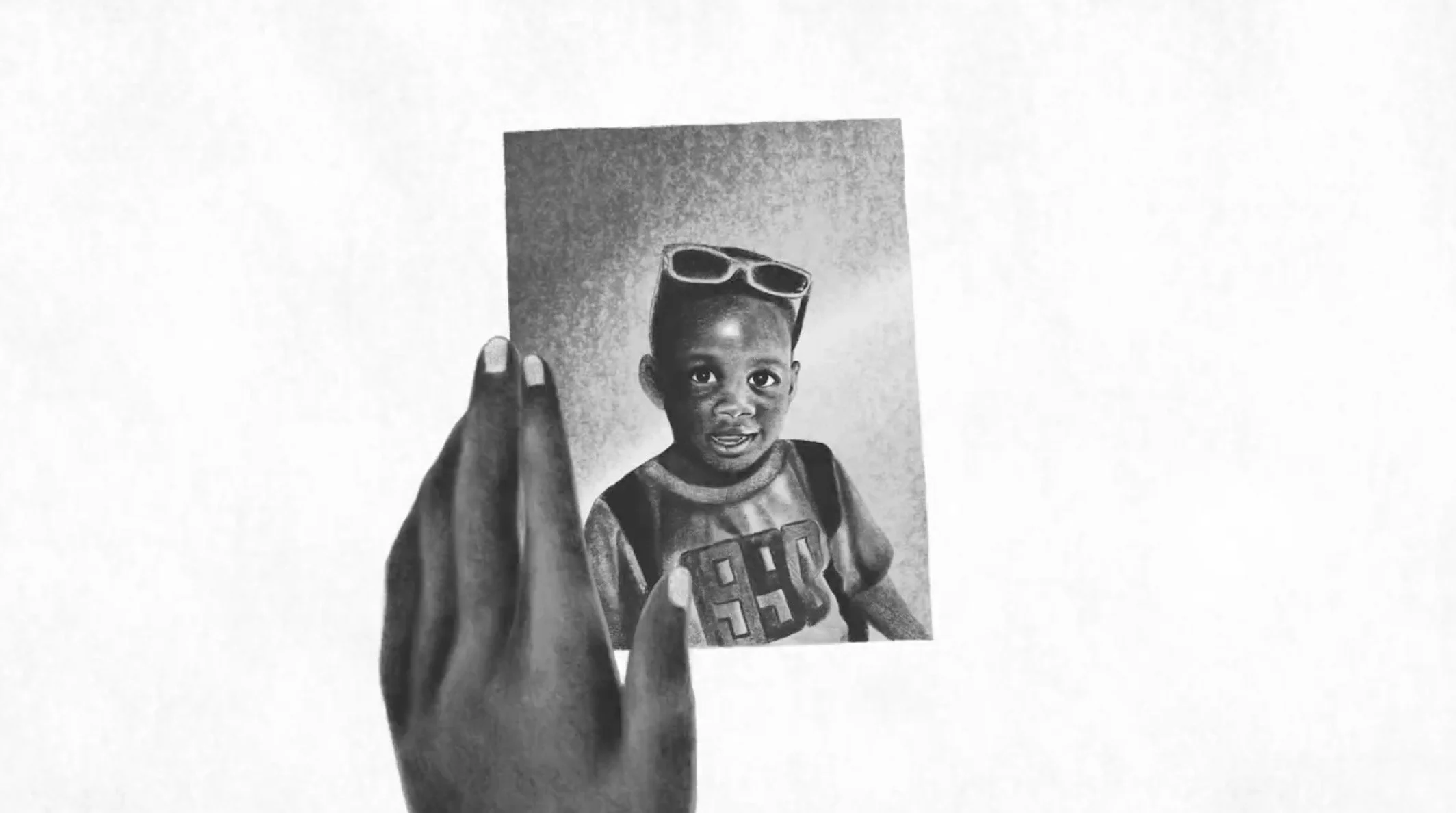

Photo by Sam Chua

“After that there was just such a high demand.” It’s not hard to see why. Suzette is a natural in front of the camera. Deep brown eyes framed by long eyelashes and an infectious laugh, she is unabated with an audience. Whether she’s on stage in front of thousands, speaking to an intimate group, or in the booth hosting her radio show, she’s made that magnetism work for her. In 2013, Suzette was a houseguest on the first season of Big Brother, where she would describe herself as, ”a cross between Oprah Winfrey and Mariah Carey”. Understandably, she became a fan favourite. Suzette has carved out a niche she can broadcast from and Indspire is just one of the seemingly endless opportunities she capitalizes on.

Vancouver styled itself a “City of Reconciliation” in 2014 and initially considered boycotting the celebrations. As Nancy MacDonald writes for Maclean’s, so soon after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission made its statements, celebrations at the expense of Indigenous culture and history seemed regressive. But the Urban Aboriginal Peoples’ Advisory Committee came forward with some alternatives. In fact, they are the only reason Vancouver is celebrating the sesquicentennial at all. A different approach needed to be taken. Canada’s Indigenous people and their culture predate confederation and so the celebrations were quickly coined Canada 150+.

There are two schools of thought on Canada 150. Many Indigenous people, especially artists such as photographer Nadya Kwandibens, have boycotted the celebrations from coast to coast. They don’t want to produce art that could be associated with the celebrations, and it is their own personal and professional line in the sand. But Suzette is of the other camp.

“There are Indigenous people using this opportunity to expose the truth. There are people like myself and other artists and leaders, who are seeing it as an opportunity to share the truth and also show them visibly that Indigenous people have arrived and we’ve been here. We’re part of society and we’re part of your history.”

Visibility is a large part of Suzette’s work. In 2003, with her husband Stanley, Suzette launched ThinkNDN, a radio program on Vancouver’s co-op radio station, CFRO 100.5.

With deep roots in the Downtown Eastside community, Suzette wanted ThinkNDN to be a “voice for the voiceless.” Not only a place to expose fresh music from Indigenous musicians, but also a place to discuss issues facing the community and to engage community members and elders in that conversation. ThinkNDN has won the award for Best Aboriginal Radio Show three years running at the Aboriginal People’s Choice Music Awards.

“I wanted to be inclusive to Indigenous people and not think about blood quantum or if you were raised in the community. Just something where they can feel pride and hear the messages of artists who are sharing their personal stories through music, through art, through poetry, through spoken word.” Blood quantum is a term used in the process of qualification of ancestry usually for the purposes of tribal membership. It remains a divisive issues among Indigenous people for its ability to both include and exclude.

Showcasing the diversity and complexity of the Indigenous people in Canada is meant to be the purpose of Canada 150+. By utilizing the sesquicentennial to showcase Aboriginal arts and culture and amplifying Indigenous voices in the discussions around reconciliation, Vancouver is trying to rebuild the relationship with its host nations and break chains of oppression latent in the system.

“I think that they made a statement across the globe with the 2010 Olympics having Indigenous people across the country be a part of the Opening Ceremonies. The reconciliation part is building that relationship and moving forward and I see that happening.” But Suzette’s not completely swayed by the “Plus” appendix to the celebrations.

“I think that there are going to be events, during this time in this country that are going to be tokenized”—actions that are merely symbolic of insincere attitudes of change instead of authentic reconciliation—“and that’s nothing new. That’s been going on forever.”

The city has three events planned. The Gathering of the Canoes, a traditional tribal canoe journey made from Jericho Beach to Campbell River by upwards of one hundred canoes, The Drum is Calling Festival, a ten-day arts and music festival in Larwill Park, and finally, a Walk for Reconciliation in September.

When asked what Vancouver can do to really take a stand, Suzette smirks. “I’m more of a radical. I have to be honest. Give back Stanley Park.” She waits for the gulp of air. “Give it to the people who rightfully own that area. Let them build a bighouse where they have traditionally built.”

“It’s almost like this country is having a birthday party on your land and you’re being invited as a guest of honour.”

The irony is palpable.

But her voice turns melancholy, even if only briefly. “But I struggle a lot too. My husband is Salvadorian. He came to this country, fleeing a war torn country of El Salvador during a major crisis, civil war. And he came here as an immigrant, leaving his Indigenous family behind and coming here because it was a safe haven for him. And so when I see him so grateful to be in this country, how can I not celebrate Canada Day for him?”

That is where the complication merely begins. As Suzette says, Indigenous people are so intertwined with society that it is hard to tease the two apart and isolate issues. They represent tradition and a history that is very heavy to carry but they also exist in a modern, “pop culture” society and the two are bound to come into conflict. Stanley and Suzette work towards the same end. Stanley—who is of Mayan descent—runs youth dances for Indigenous youth through the entertainment company he and Suzette own together and is often the production director behind Suzette’s presentations and speaking engagements. He is a fully adopted member of Suzette’s community. The couple even appear together on the branding posters for the Aboriginal Cancer Care Society.

Aboriginal Day is where the crossover happens. While Canada Day is a day where Suzette and her family prioritize getting outside together and spending time in nature, Aboriginal Day, June 21, is the true expression of cultural pride.

“Aboriginal Day is a huge celebration. I think that’s more important. Even my husband, he celebrates with us. We make a big deal of it.”

Vancouver has its own National Aboriginal Day celebration, hosted at Trout Lake with additional performances at Canada Place. There are live musical performances from First Nations, Inuit and Métis artists, pow wow dances, reenactments of Indigenous myths, drum making workshops as well as booths with food and handmade goods such as beaded jewelry, carvings, paintings, jewelry and clothing designed by Indigenous artists. Last year was the twentieth anniversary of the holiday, established in 1996 by then Governor General Roméo Leblanc.

“I wish it was like Black History Month, you know, where we get a whole month. Truth and Reconciliation would mean to honour that and make it a national holiday. That would be the real way of moving forward.” Suzette’s hope is that through it being a national holiday, more conversation and education could happen about Indigenous people and their culture in Canada.

“In Washington State, they changed the name of Columbus Day to Indigenous Day. They know and acknowledge that Columbus had a hand in all of these atrocities. And you can’t celebrate that.” A number of the states in the U.S. have taken steps towards reconciliation, though reconciliation efforts are just as complex, with Standing Rock and the Washington Redskins debacle ongoing. Canada is on its way. Even in terms of the Canada 150+ occasion, city council committed to ask for permission from the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Watuth nations to hold a “civic celebration”. As of January, two out of the three had signed with the third considered to be “imminent” according to Marnie Rice, a cultural planner for the city.

Suzette says, “I think that there’s a huge part missing and that’s the part that’s called the Truth when you’re talking about Truth and Reconciliation. To build a relationship, you need to be sympathetic, understanding and educated on the truth of what this country did to our people.”

Suzette works hard with her own children, ages 16, 13, and 5, to educate them about Indigenous issues, citing residential schools, Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), IdleNoMore, and the BlueDot movement, a David Suzuki initiative petitioning for the legal protections for clean air and drinking water with a focus on Reserves. The history and impact of residential schools was formally added to the Canadian school curriculum in 2015 but when Suzette asked her son, who is in high school, about MMIWG, he said they didn’t learn about that in school. Suzette and her family live only blocks from Main and Hastings, a neighbourhood central to the atrocities.

“I have three kids and I have to work hard to make sure that they are aware of these issues and that they understand it because they are up against these things every day as Aboriginal young people.”

She’s grateful for her community on Commercial Drive and in East Van. She credits the diversity of cultures and the universality of struggle with creating a caring environment, not just in schools but among regular people as well, a culture of less prejudice and more understanding.

“I know what it was like for me as a visibly indigenous person. I had to have thick skin from an early age. So I train my kids to have confidence and education.”

That seems to be at the root of Suzette’s focus. Her role as a wife and mother exists in tandem with her identity as an Indigenous woman and a member of the community, working to create better opportunities for the next generation of Indigenous people.

The reality for Vancouver and for the conversations surrounding Canada 150—and it’s 150+ counterpart—is these histories exist in constant tension. That is what makes Reconciliation so tricky. That is the existent reality of Canadian life in the new age of Truth and Reconciliation. “Decolonization” and “Indigenization” are terms that are bandied about under the banner of reconciliation among intellectuals and activists alike, but at the end of the day the goal is a complex (and at times, elusive) coexisting.

Ginger Gosnell-Myers, the city’s first manager of Aboriginal relations said, “None of us is going anywhere. We have to learn to live together; in a respectful way, and in a truthful way.”

Suzette Amaya contains multitudes. She is at once urban and rural, traditional and contemporary, her indigenous identity—as it is with all other Indigenous people in Canada—an amalgamation of the pain of the past, the present uphill battle of passive racism, and a future focused around healing from the past and creating a better, more equitable society.

It’s leaders in the Indigenous Community like Suzette Amaya who are opening Indigenous arts and culture to the Western world, when it would be so easy to shut it out. They are the ones to keep perspective, remain hopeful, and have pride. Suzette finishes with, “My cheeky little self says, ‘I’m gonna show you a Native person. I’m going to share with you their music. I’m going to show you that we are here, we’re strong and we’re resilient.”

If you'd like to learn more about the Indspire program, you can head on over to their website here. If you want to keep up with Suzette and her many endeavours, you can find her on Twitter at @SuzetteAmaya.