1000 Parker: The Past is Present

/Just getting to East Vancouver’s 1000 Parker Art Studios takes us back in time. Prior Street, not yet marred by gentrification, is lined by original wooden Vancouver homes circa late 19th century that still watch us with their flat wooden faces as we drive passed; there is a smattering of the notoriously humble “Vancouver Specials”; and then we have to cross the tracks, and yes, often there are trains blocking our way. Amidst the relentless ding-ding-ding of the train-crossing bell, we have no choice but to slow down, breathe deeply and attempt to stop the whirling of our fast paced millenial minds.

1000 Parker Street is located on land known as False Creek. This land was originally mud flats that were a vital food source for the Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish First Nations. It was in-filled by Canadian National Railway in 1913, and by the 1950s it was the industrial heartland of Vancouver with sawmills and port operations. In the 1930s, it was a garbage dump. 1000 Parker Street manager, Terry Laufenberg, told me that bottles dating from the early 20th century can be found when one takes the time to dig.

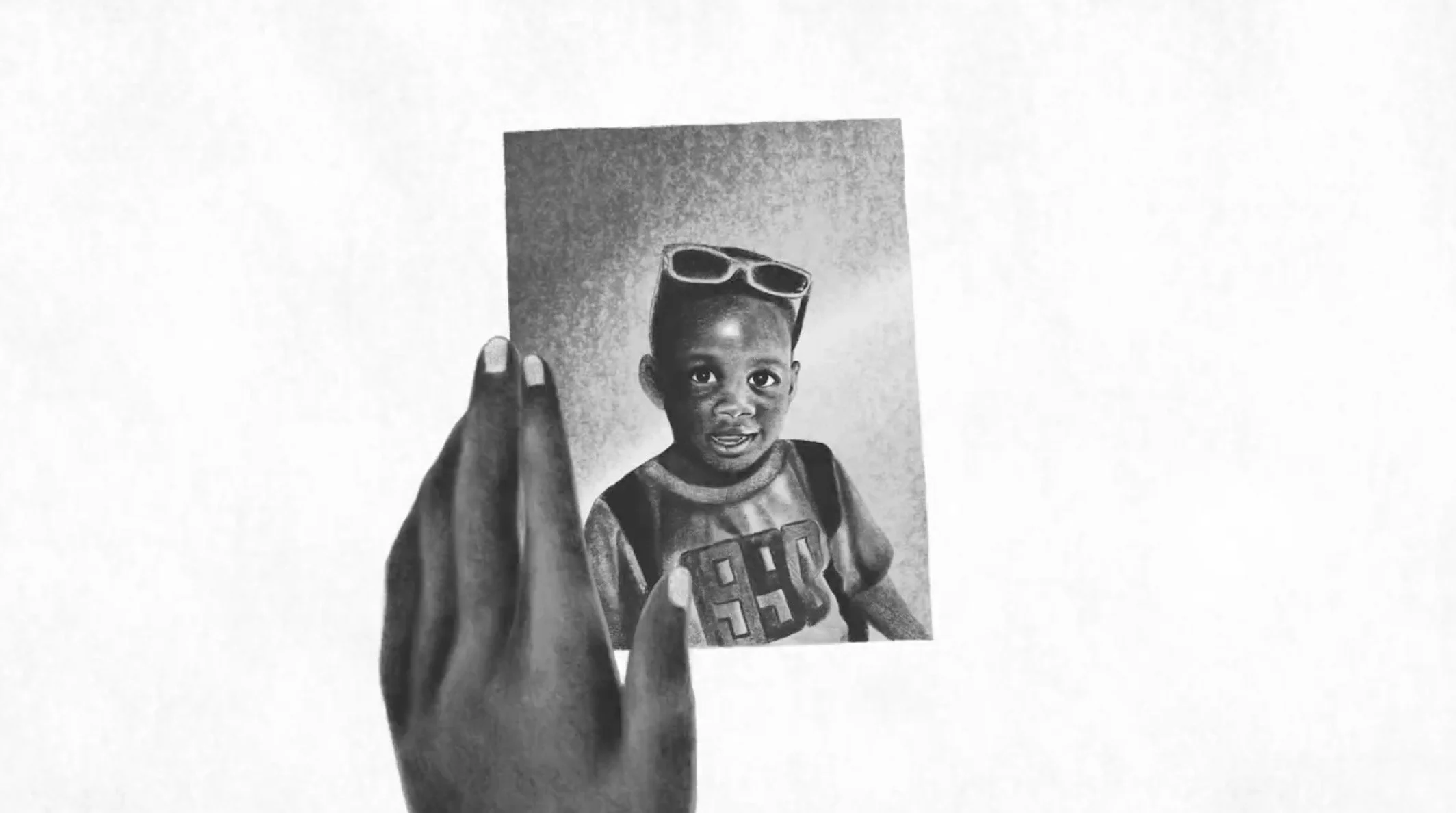

Photo by Carylann Loeppky

The building was home to the Restmore Mattress factory until Keith Beattie purchased it in the 1980s. This was the beginning of the Beattie Group’s Real Estate Empire. During the early Beattie era, it was used as warehouse space for a variety of local businesses including Vancouver’s famed Woodward’s stores. The early 1980s recession resulted in the four-story building being progressively divided into artist studios. When I asked Terry Laufenberg how many artists have studio space at 1000 Parker, he said “it is impossible to know exactly because each of the 110 studios provide creative space for anywhere from 1-15 artists. They all pay the rent collectively.” With so much creative energy in one location, it is not surprising that 1000 Parker is the hub of Vancouver’s East Side Culture Crawl with an average of 30,000 people exploring its labyrinthine corridors each year.

The artists at 1000 Parker create in a cultural heartland of the city. Artists Kyla Bourgh, Laurel Swenson, and Suzy Birstein are three of the hundreds of artists who have studios there. Bourgh’s latest project plays with found objects, both literal and figurative as she collages glamour portraits of women from the 1930s and 1940s onto the pages of quintessential “boy books” like The Hardy Boys. Swenson’s new paintings haunt the present with an impending apocalypse. Birstein’s ceramic sculptures are self-portraits that enact lineages between past women and goddesses within a present self. Like the historic building that provides their creative space, these three Vancouver artists incorporate the past in order to create representations of the present.

Kyla Bourgh, “Partial Portraits 1”, from the series Partial Portraits

Kyla Bourgh, “Partial Portraits 2”, from the series Partial Portraits

Bourgh tears pages from the found object ‘boy books’ and re-interprets the style of glamour photos from the early to mid-twentieth century. Composed of past textual representations of the perfect boy-child and images of what was once considered the “ideal woman”, Kyla Bourgh’s “Partial Portraits” are palimpsests of gender. However, despite the density of subject matter, Bourgh often reveals by way of what is left out. The glamourous women of yore are sometimes only eyes framed by the shape of a particular era’s dreamy hairstyle, sometimes merely lips delineated by the hint of a chin. And yet, these erasures don’t matter: we know these images by heart. The gaps in what we know are filled with equally familiar text and, in some of the portraits, both are cancelled out by electrician’s tape, another piece of paper or a heavy slash of paint. The revelation and erasure of past gender ideals creates a dynamism that complicates the construction of femininity and masculinity not only in the past, but also in our contemporaneity.

Laurel Swenson, “Apocalypse Head 4”, from the series Apocalypse Portraits

Laurel Swenson, “Apocalypse Head 5”, from the series Apocalypse Portraits

Laurel Swenson told me how her series “Apocalypse Portraits” are influenced by past depictions of future dystopias and the political darkness that she feels is pervading our current times. Using acrylic, polymers, and powdered graphite on cold press paper, Swenson strives for the loosest, ‘barely there’ marks in a limited colour palette. Faded blues and hints of military green punctuate blacks, whites and greys. The images fall apart as apparitions that begin to fade upon their apprehension. The unrestrained technique and lack of detail give us expressions that burst with possibilities of what has happened, what is happening, and what is going to happen next. Like Bourgh, the narratives of Swenson’s dark figures are told through their brevity. The viewer is invited to both recall and predict the gaps.

Suzy Birstein, “Bird Whisperer”, from the series Tsipora

Suzy Birstein, “Pink Tutu”, from the series Tsipora

In contrast with Bourgh and Swenson, Suzy Birstein’s ceramic series, “Tsipora,” compounds excess. She explained to me “I have a philosophy to ‘notice what I notice.’ When I find something that intrigues me, I bring it home. It’s whatever fires my imagination and touches my spirit.” The artist references historical women and popular culture in order to build composites of a current ‘self.’ She channels an eclectic mix of past female powerhouses like Frida Kahlo, Queen Nefertiti, Carmen Miranda, Gelede, Catrina Calaveras, Ganesha, South Asian goddesses, Athena and Acropolis Korai, and Alice in Wonderland. The women are ecstatic, gazing at the viewer through layers of past knowledge. Using fired clay, patinas, engobes, oil paint and bindis, Birstein builds surfaces that glow with the wonder of anthropological artefacts. The women are simultaneously ancient, recent and new, beckoning us to remember the past at the same time as having a heightened awareness of now and looking to the future.

In their acts of creation, Bourgh, Swenson and Birstein are all guided by their art process. When asked if they have fixed plans when beginning a project, Birstein explained, “I do not have a sense of the outcome. The not knowing and the discovery is what is most stimulating to me.” For Swenson, “each painting emerges over time with layers of texture, marks, colour, and materials in a call-and-response-like manner.” Bourgh, on the other hand, does have a set starting point with the tearing of each page from a specific book; however, the selections of the pages are intuitive and, after the placement of the textual foundation, she described how “then I disconnect from too much pre-planning and I add, at random, paint and collage elements. This mark making sets the stage for the images.” Like history informing the present, it is what came before that decides the lineage of future action.

For both the artists and the viewer, art is an adventure of excavation—but it doesn’t always come easily. Like the decades of history that resulted in the building that is now 1000 Parker, it is the artist’s patience and instinct that results in the final work of art. However, art is never still; like the continued evolution of a city or an historic building, art is alive with process, and it doesn’t end with the artist: each viewer’s encounter adds another layer of creation. In contrast to the surfaces we skim in the race of modern life, art shows us how we need to dig into the past in order to fully experience our present. And, like the drive to the East Side’s 1000 Parker, we may have the privilege of initiation as a tedious train crossing forces us to stop, wait, and breathe along the way.

More information regarding the Eastside Culture Crawl can be found on their website.

Visit Kyla Bourgh's website here.

Visit Laurel Swenson's website here.

Visit Suzy Birstein's website here.

www.karenmoe.net