Review: The Decalogue (Dekalog) at the Cinematheque

/Still from Kieslowski's Dekalog (IX)

After three instalments of Kieslowski’s Dekalog (1989) you feel like you’re inside a crossword puzzle. Each of the ten episodes has a clue: it’s a specific Commandment. The answers aren’t predictable. But if you persevere with the lines and twists, there's reward. Dekalog presents unexpected ways of seeing the ordinary.

A crossword, like a film, is a hopeful bargain between makers and consumers. You can start anywhere and you don’t have to attend in any order. Dekalog is unlike a conventional TV series. You notice that the clues start to intersect. You realise that the parallels between clues coalesce into a fuller composition. Some of these parallels arise because characters appear in two or more episodes. Some of the counterparts are visual enactments; some are thematic riffs. Some are just ghosts that echo through the cast and crew. They endure across neighbourhoods, occupations, generations and individual memories. These coincidences thrive in Dekalog. You'll want to remain in the puzzle long after it's finished.

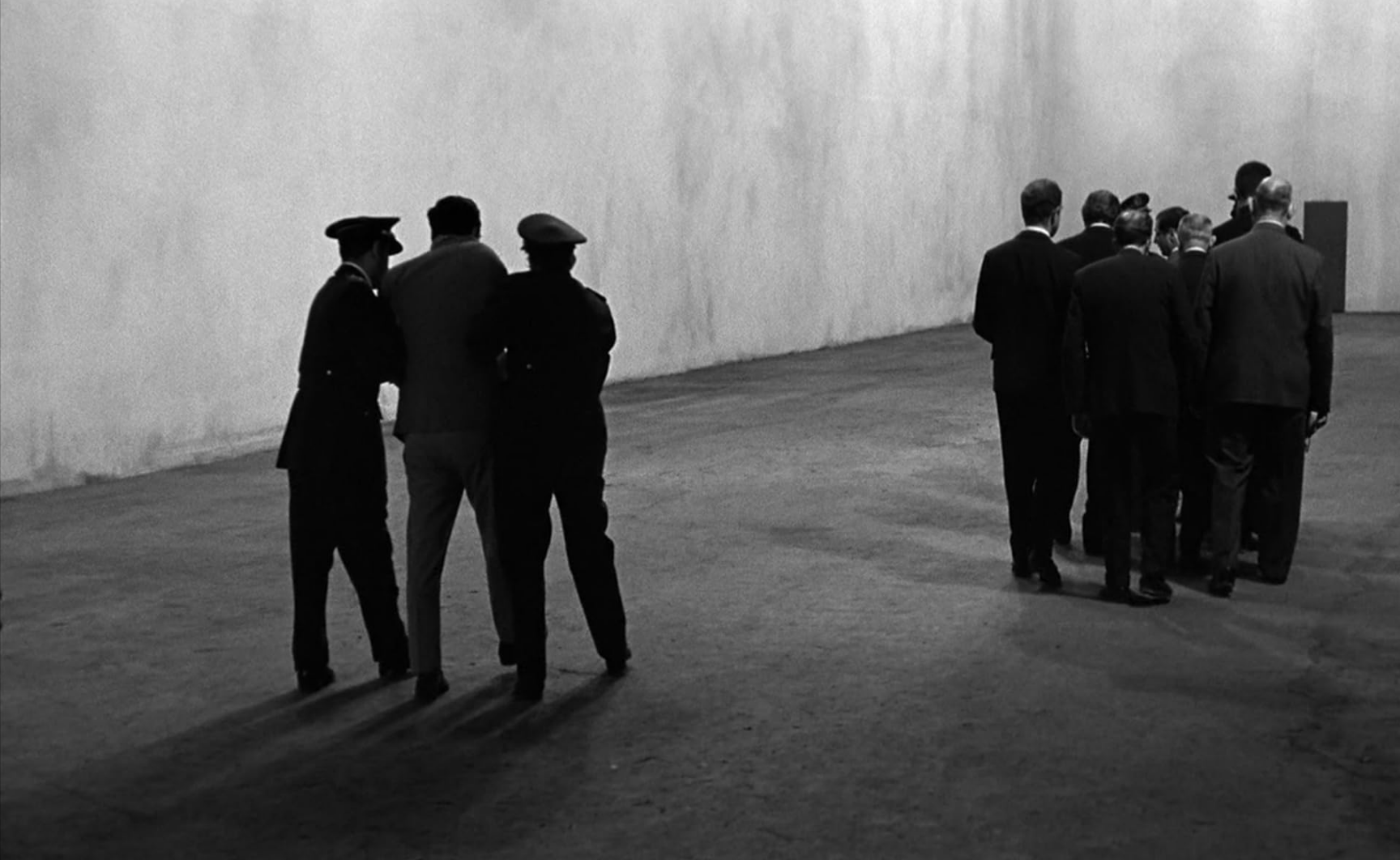

We can recognize parallel symbols of interruption in any episode. There’s a picture frame that won’t hang straight (VIII). There’s a computer that activates at unsuitable moments (I). There are cracked pipes that drip and irritate the hospital patients (II). There’s a curtain that blocks out hanging executions (V). The curtain rings snag and it’s an impediment that an officer rips to the ground. What do these objects want? Kieslowski acquaints the audience with the secret power of objects. It might move us to respect the unconscious.

Accidents disturb the Dekalog characters’ sense of control - over themselves and others. They believe their customs and technologies will insulate them from the unknown. The heroes and heroines seek impossible control. It’s ridiculous in proportion to the empathy you feel for the character. Jerzy and Artur become infatuated with a plan and neglect their social responsibilities (X). They obsess with safeguarding and diversifying their father's endowment.

Dorota harasses her doctor-neighbour for updates on her husband’s condition (II). There are boxes behind the doctor when he's giving Dorota sworn prognosis. The boxes display the word confiance, which means trust or faith in French. Dorota decides her future in accordance to the medical advice. In Episode I, the father is confident in scientific calculation as a guarantee. He measures the sturdiness of the frozen neighbourhood field. But when his son Pawel doesn’t return home from skating, Krzystztof slips into meltdown. If you've ever depended on a smartphone and then lost or broken one, you’ll see yourself in the father's gradation of shock.

Still from Kieslowski's Dekalog (II)

Dekalog contrasts techniques of official investigation against informal hopes of knowing. Kieslowski’s films dance around the limits of rational and intuitive modes of understanding fate. Episode V is a chilling exposition of this. We see the personal and institutional approaches to knowing a murderer.

Dekalog also underscores the power sought from obtaining knowledge by prying. Secrets are the fulcrums where power relations plummet and climb. In Episode VI Anka discovers a grave letter among the father Michal’s belongings. She steals it and ponders the possible outcomes. The viewer doesn’t know what Michal already knows, that Anka will find it. It’s a quandary when we know something below the surface. What will we admit?

The films are extraordinary because they linger in the indulgence of espial. They touch on the thrill of knowing more than someone else.

The first Kieslowski film I saw was Gadajace Glowy (Talking Heads). Our lecturer helped us appreciate Kieslowski's warmth as a filmmaker. The documentary evinces the dignity of the interview subjects. It asks fixed questions about everyday Polish life. Yet somehow it captures the surrounding air in the interview settings. It is precious and charged.

Kieslowski’s detailed grounding in documentary informs the continuity of surveillance in Dekalog. We watch unwary figures from afar all the time. These moments appear as glimpses in their mundane routines. The seen matter has relatable urgency. We stare through transparent surfaces, slits, oblique and irregular frames. It does not feel like we are stealing access and gaining control over a stranger. Though we must know we are. It seems like a compulsion.

It would be hypocritical to prescribe against passionate spectatorship. Dekalog is an obsessive observation itself.

And that’s why Kieslowski embeds character Artur Barcis in every installment. The mysterious young man witnesses critical story moments from within the scene. He is the eye of the storm. What's his business there? Is he a proxy for the master author? Is he representing the audience as impotent observers? Is he a symbol of unknowable otherness? He stands by with ambiguous expressions and is allowed no dialogue.

Kieslowski’s Dekalog doesn't feel as corrective as the commandments it’s modelled on. It follows and describes the volatile ‘being’ of a body, without judgment. We inhabit pleasurable delusions of abandon. They are not shameful lessons. Episode III might be my favourite cinematic portrayal of useless, fanciful adventure. Ewa confesses to Janusz, “there’s been a few lies today.” There’s something human about wanting what’s impossible and pretending, for a while, that it will materialize. Kieslowski's project preserves accounts of everyday souls more than it advocates ways to live.

This series is reminiscent of a balanced short story collection. The freedom of different cinematographers affords a rich mix of tones. The vignettes are efficient and cogent. The whole work provides uplifting and plaintive conclusions. The episodes end like weighted short stories: after the plane has begun nosediving. There is always more than one character who will confront the complex problems in the aftermath. It’s hard to imagine a TV series like The Wire without this precedent.

The moral mess that we’ve spectated is salutary. This point of no return, which might become catharsis, seems key to Kieslowski’s enterprise. The stories bring difficult losses of innocence and even material sacrifice. The community of relations must confront what was hidden to heal and grow together. Greater openness for their future is the only consolation. Dekalog testifies to human confusion and the unavoidable collisions of fate. It is not urging virtues or spiritual cleanliness. So what does this portrayal of sin do? It enlightens. It pries open your outlook and makes you empathise with being.

You exit the cinema for intermission and the first thing you see is a Criterion Dekalog poster in the lobby. It shows a cluster of ten black boxes printed, uncannily, like a crossword. But is this appearance a coincidence or just confirmation bias? Or maybe you’ve somehow observed this poster already and it’s only now registering? Or is it supposed to be a neo-crucifix or a misshapen tetris piece? This association of boxes is the luring complex of the film.

Still from Kieslowski's Dekalog (VI)