Review: Brian De Palma at Vancity Theatre

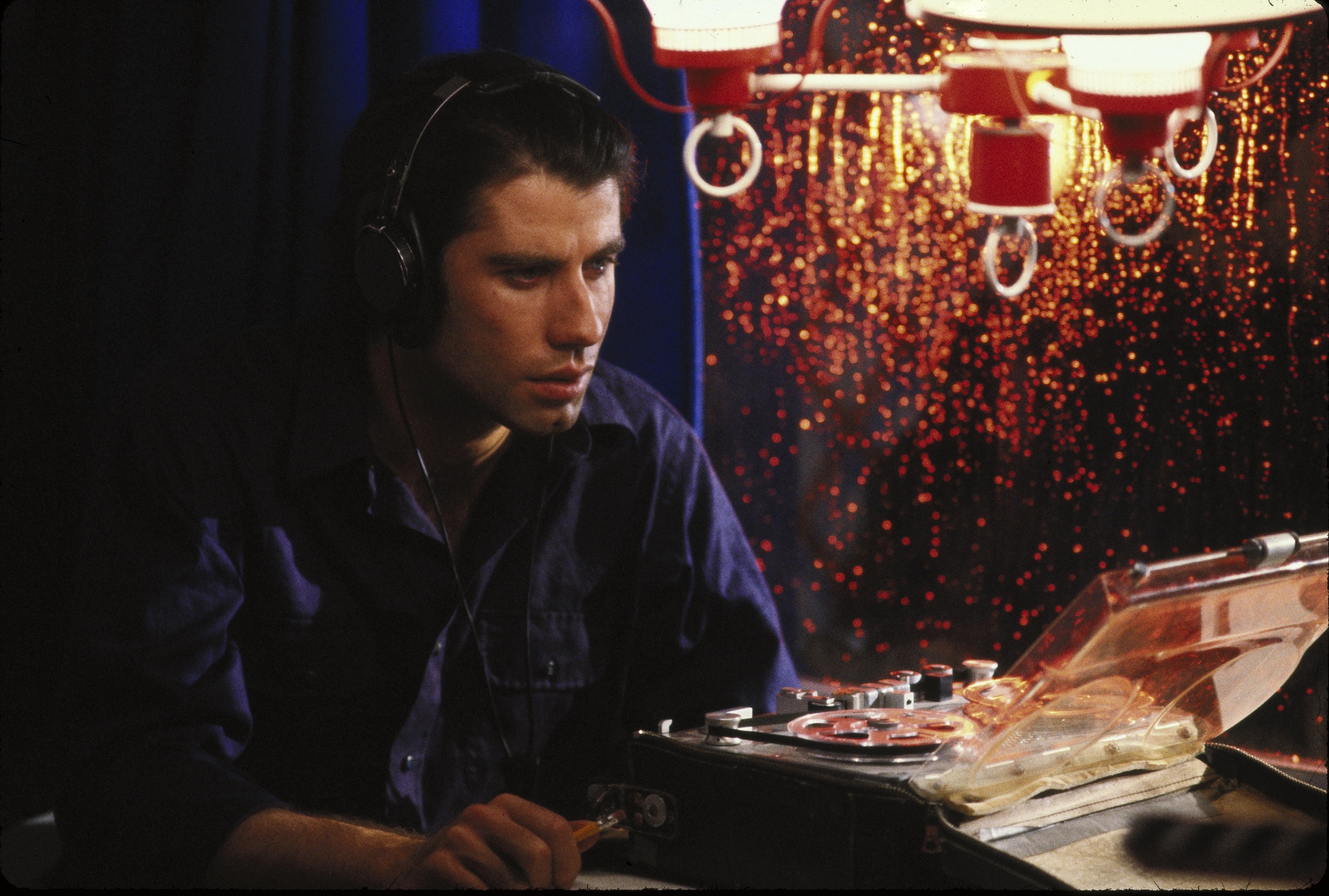

/Film still from Blow Out

It is a very specific thing, to watch movies. You isolate yourself within another world, tuning your senses to whatever the film chooses to reveal. You suspend disbelief, forgive character flaw. You gather your favourite snacks. The whole deal. Of course, there are movies which are more captivating than others, but that’s not meant to be discouraging. Finding those cinematic gems is all part of the fun. And boy, oh boy, do they ever sparkle!

The Brain De Palma retrospective, hosted by Vancity Theatre and which took place from July 1-20, was a pocket-sized version of said film hunt, an opportunity to unearth both the duds and the diamonds of De Palma’s lengthy career. His fascination with film began while at Sarah Lawrence College, where he made several short films, and later his first full-length feature with a fresh-faced Robert de Niro. The following four decades of filmmaking proved to be erratic for De Palma, as his films either plummeted in the public eye or garnered wide success—hardly any compromise. However, the older his films get, the more cherished they become, and it is for this reason that Vancity’s retrospective was so popular. That, and a handful of screenings of Noah Baumbach and Jake Paltrow’s new documentary on the illustrious filmmaker.

Film still from Phantom of the Paradise

I managed to catch nine out of the total fourteen films, including the De Palma (2015) documentary. The barrage of specific De Palma style and story-telling was both exciting and tedious at every turn. Some films were cheesier than I remembered, some just as risqué. But this divide between schlock and refinement is what, I think, defines De Palma as a filmmaker. He is all at once a Hitchcock-ian traditionalist, a technical wiz, and a so-bad-its-good supreme-o. You couldn’t trade one for the other—his movies are singular because of their twist between critical acclaim and Razzie status.

Sitting in the theatre amidst a crowd so obviously dedicated to Brian’s subjective genius was a thrilling experience, I must say. You could feel the admiration flowing through the seats, and every bit of camp and sass onscreen was met with pure delight by nearly all. It’s true—allowing myself to get immersed in the specific flair of De Palma was a treat, and a wild ride. Yes, there were some less-than-morally sound moments and a definite obsession with sexy ladies, but that’s genre filmmaking, right? Questionable, but all the same, De Palma’s cinema is hard to tear away from.

Film still from Obsession

In Baumbach and Paltrow’s filmic conversation with the director, De Palma says that “directors make magical illusions”—they mingle forms of disguise, deception, trickery and image to dazzling effect. It is clear in his films that De Palma takes this dear to heart. Duality abounds in his characters, driving the story and thus adding themes of false self, reversal and duplicity into the movies as a whole. This obviously Hitchcock-inspired motif is evident in nearly every one of his films, particularly the earlier ones. Body Double (1984), the story of an unknown actor as he tries to piece together trails of murder, sex, and corruption while battling his extreme claustrophobia, is practically a collage of scenes and themes from Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958). In Obsession (1976), a young woman falls into the charms of a grief-stricken man, who decides to mould his new lover into his past wife’s image—a plot practically cut and pasted from Hitchcock’s Vertigo. De Palma’s Dressed to Kill (1980) lifts from Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) in its following of a man obsessed with dressing up in traditionally women’s garb and knifing people. These examples may seem horrendously cliché on paper, but on screen they were enticing and fresh (Dressed to Kill is perhaps the exception to this; it was often overwhelmingly transphobic, so I might exclude it from the “fresh” label, and give it “cringingly dated” instead). The overt reference to past films only added to De Palma’s campy, stylistic rendering of human desire and its downfalls. The nods to good ol’ Alfred persisted even in films such as Phantom of the Paradise (1974)—possibly my favourite De Palma film, with a killer soundtrack to boot—where the famous Psycho shower scene was recreated with a glam-rock diva and a plunger. Or in Blow Out (1981)—my second favourite De Palma flick—the 360 degree tracking shot during John Travolta’s frantic search of his apartment is certainly reminiscent of the 360 degree shots in Vertigo or The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956). These gestures of homage are examples of De Palma’s investment in cinematic tradition, and the methods of madness which film fosters and is fuelled by.

Film still from Body Double

Another specific aspect of De Palma’s films is his technical signature, the split-screen. Tying in once again with themes of duality and abstraction, the split-screen connects, distracts, and alienates viewers within the film’s image, as we see two perspectives play out at once while also drawing meaning between the two. One of the most prominent examples is the turbulent prom scene in Carrie (1976), as we watch high school kids scatter in fear on one half of the screen and Carrie’s wide, flashing eyes on the other. De Palma mentioned in the documentary how, though often touted as technically ambitious and too intellectual, split-screen felt right for his films. I agree with him; the editing technique is a manifestation of theme, taking the story’s implications one step further while also giving us more to look at and unpack.

Film still from Dressed to Kill

Yes, there were a few films which fell short of excellence. But there were also gems worthy of a third or even fourth watch. As said earlier, this is Brian De Palma’s triumph, the gamble you take when you watch one of his movies. If you decide to snuggle up on your couch with one of his creations, don’t assume you’ll be able to guess where he’ll take you. De Palma’s films spin you in all directions, flipping supposed truths over to reveal sleazy, campy, sickeningly vibrant underbellies. Of this you can be sure.