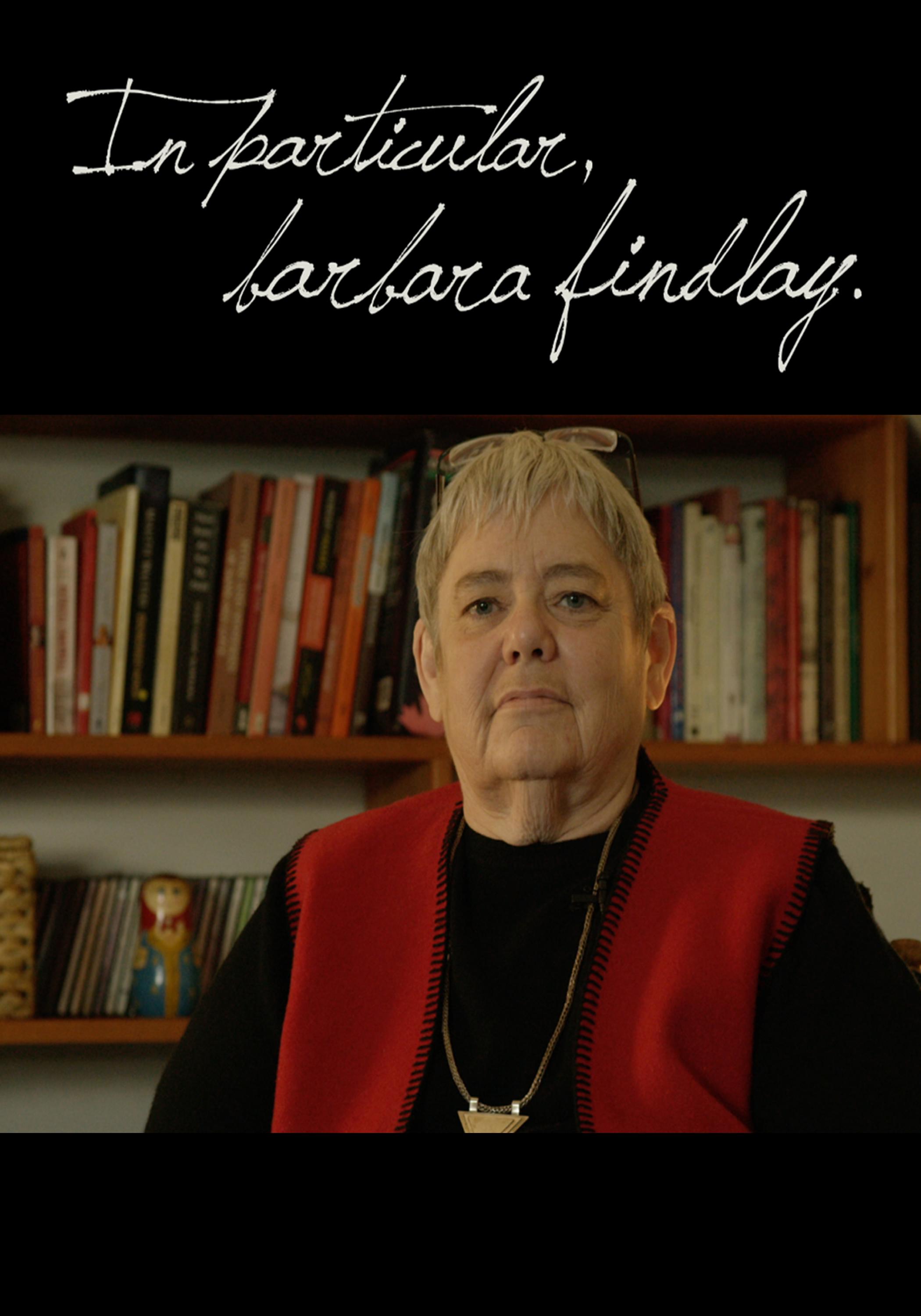

Review: In Particular, barbara findlay at VQFF

/Becca Plucer's In Particular, barbara findlay

Normally a biopic has to track through loads of plot and narrative before we feel one way or another about the personality on screen—first impressions take longer through flat display screens—but for whatever reason, with barbara findlay (lower case intentional), subject of biopic In Particular, barbara findlay (directed by Becca Plucer), it feels like you know her after just a few frames. This is someone who’s magisterially calm and collected. She’s cool. She’s empathic. She’s trustworthy. And she’s wise (I don’t like this word either, but, trust me, it fits). Another way of summing up her qualities is to say that findlay seems hyper-sane—more sane than almost anyone that comes to mind—so it’s surprising to learn just a few minutes into the doc that she's been diagnosed with a mental disorder, undergone psychoanalysis, tranquilizers, and mental institutions. Actually, it’s a bit enraging. If this is what mental illness looks like, something’s gone wrong. And this is what the movie’s about—findlay happened to experience, first hand, that something was wrong with mental institutions and the state of minority rights, and she made it her goal to fight back against it, reform it, and help those who’d been the victims of state power.

This is what happened:

Growing up, findlay was viciously intelligent. She was a book person. Before entering school, she spent most of her time reading books. In elementary school, she also spent all of her time reading books. By the time she was in high school, she had four younger sisters, but we don’t learn much about them. Instead we hear about her grades (all A’s), and her Hermione Granger-like dedication (she once read everything Steinbeck wrote to write a small paper on one of his novellas). Evidently, she was a precocious student. And her life followed the standard arc of overly precocious children: she graduated with high expectations, moved to a prestigious university, and then had a breakdown.

When she recounts her own rendition of this story, findlay is two parts sad, two parts (indignant) mirth. Sad for obvious reasons: the breakdown began when she told a psychiatrist at her university that something might be wrong with her—that she was attracted to girls. His response was immediate: First she was locked up in the local nuthouse. Then she was told she had a mental disorder (being a lesbian was, by definition, a mental disorder; this was a time when Homosexual Panic Defence was a legal ruling—look it up). Mirthful because of how absurd it all was: Once, for instance, during her time in the nuthouse, she was hired to help prove why women could never be engineers—a strange enough project on its own—only to find that the real project was matchmaking and that she was the test subject. If this sounds like a plot someone would use to cause insanity and not to cure it, I agree. It’s not for nothing that findlay’s partner still wears a shirt with the print “still sane” on the front.

The documentary could just be about this. How did barbara findlay stay sane given the circumstances? How did anyone gay make it out okay? But the movie focuses less on how she got through it than what she’s done since.

She’s done a lot since:

She’s co-created the December 9th Coalition, an organization based on increasing Queer public visibility. She’s been involved with many unpopular legal cases defending LGBTQ. She’s won the The Hero Award from SOGIC; the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal; the Award of Merit. In 2001 she was designated as Queen’s Counsel, an award from the queen to the most distinguished members of the legal profession. The list continues, and I’m tempted to continue it here. At the same time, I’m aware how this sort of praise can seem lifeless or abstract—who knows what the criteria for choosing the Queen’s Counsel are—and I’d like to say this is precisely what makes the documentary so useful: it makes a hero out of someone in a profession made up of tiny print and footnotes and clauses and subclauses and sub-subclauses, something that is by definition almost impossible to make entertaining, but is undeniably important. It puts a heroic face to a (subjectively) boring profession.

There are lots of ways to rebel. For whatever reason, the one’s we hear about tend to be loud and angry. They are the rebellions of cuss words and picket lines, which are probably important. But findlay’s form of rebellion is refreshing. It trims the fat — it takes the fashion, the sexiness, the hipness, out of rebellion. What’s left is a women at a table most nights, learning about the law and taking up cases. And, I have to say, it comforts me that there’s someone like findlay behind the scenes, doing her all to change the small print on the legal documents that do radically change our lives. Here’s someone worth idolizing.