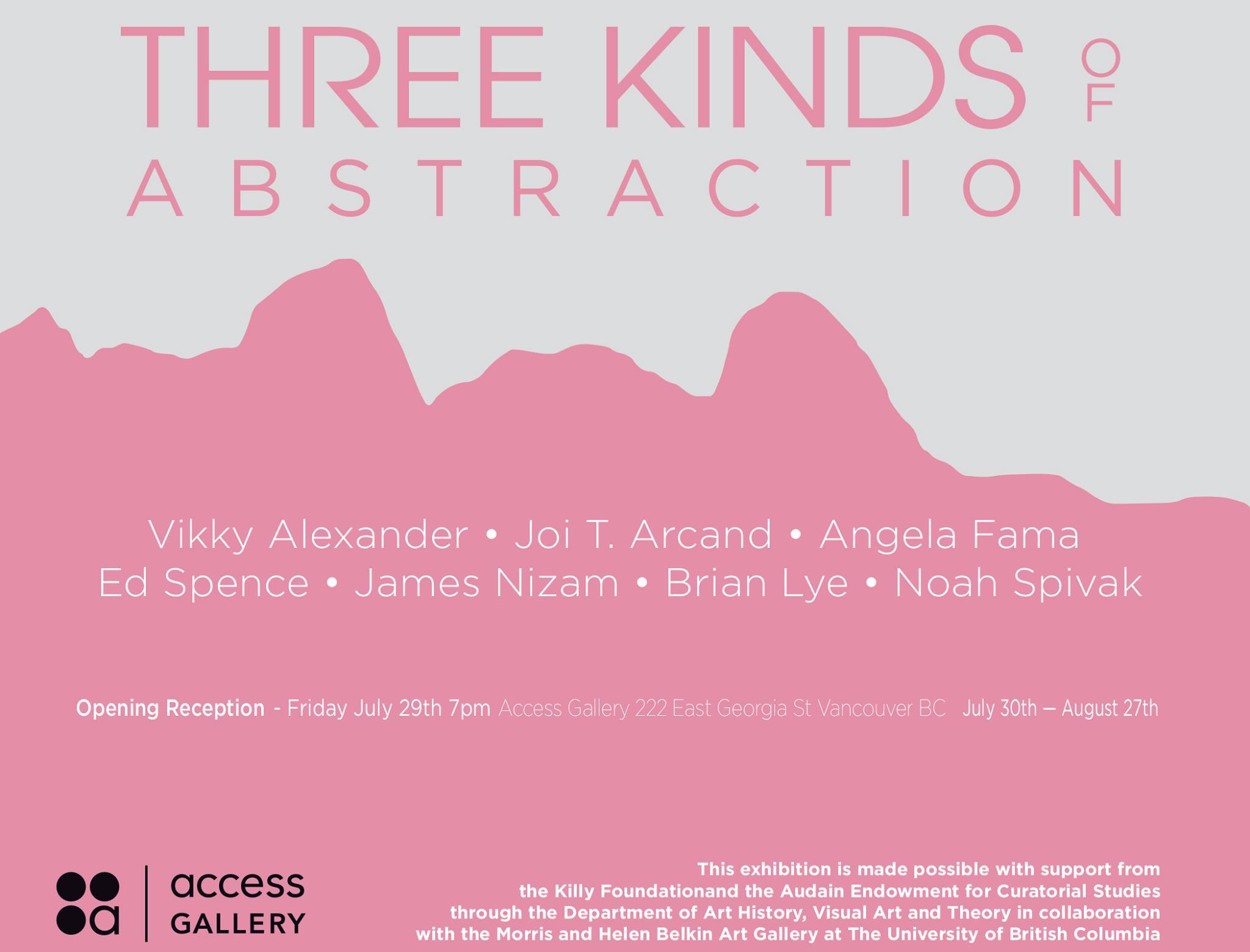

Three Kinds of Abstraction at Access Gallery

/April Thompson, after an internship at the Frick Collection in New York and an undergrad in Australia, booked a vacation to Vancouver. “I got here and thought, this place is just like a Jeff Wall photograph.” After years of curiosity, she knew it was time to stay. Thompson cancelled her return ticket and sunk her teeth into the Critical and Curatorial Studies Master’s program at UBC, soon coming to the realization that the Vancouver School is not what it at first had seemed. Her thesis exhibition, Three Kinds of Abstraction, opens at Access Gallery on July 29th, 2016. We met up at Turk’s on Commercial to talk the process, the theory, and the abstraction of abstraction.

Megan Jenkins: Where did this show come from?

April Thompson: I knew I wanted to do a show on photography. Compared to what I wanted to do initially, though, the show has changed so much. It’s very different. Initially I wanted to challenge the centrality of the Vancouver School as a mythic school, which is ironic because my whole Jeff-Wall-attraction to Vancouver was totally false. I also just wanted to unpack it because I’m so interested in it.

The show went through a lot of critiques and defenses as a part of my program, so the past 12 months of preparation have been about refining. Some people put on a show in a month, and I don’t know how they can do that. I needed the slower process before I felt confident with the show.

The curatorial program at UBC is great because it gives you a chance to be practical but it’s still serving so many other things. There’s so much theory involved, it’s very mediated, there’s a lot of facets and people that you need to think about.

MJ: That makes sense, I mean, because as a curator, you’re likely going to be appeasing donors or directors for most of your career.

AT: Definitely. Curating has become so visible, and the transparency is important but it’s also becoming increasingly bureaucratic. You really have to defend every decision you make.

MJ: How many artists are involved in the show?

AT: There are 7 participating artists. My show is trying to challenge the idea of a “local artist.” If there’s any proposition in this show, it’s that there’s no such thing as a local creative spirit. Especially in global capitalist cities. I don’t think that can be easily defined.

So all of these artists at some point have been in Vancouver and have photographed in Vancouver, but that’s not to say that their work on display is from Vancouver itself. Noah Spivak is in Australia now but his works in the show are from his time here. Joi T Arcand doesn’t live in Vancouver anymore, but was at one time working at grunt gallery. Vikky Alexander has just moved her studio to Montreal. So at some point, these artists has passed through Vancouver but that’s not to say it has necessarily defined their works.

MJ: My impression of the local spirit, if there is one, is that artists practicing in Vancouver are not yet at the top of their practice.

AT: It’s a very transitionary place, and I think it can own that. Vancouver historically has been criticized I think for lacking a cohesive feeling or an identity, because it’s been rebuilt many times and is always in a state of flux. But I think artists are responding to that in a way that’s really interesting.

MJ: If there’s any place to experiment with your practice, I suppose it would be here. Especially with our art scene becoming more receptive and innovative. It’s a good place to mess around.

AT: That’s a great slogan. “Vancouver: A good place to mess around.”

MJ: So the show is at Access Gallery. Do you have a relationship with Access?

AT: Vancouver has a lot of artist run galleries and centres, but they can be sometimes be inaccessible. In the Masters program you begin to look at galleries you might want to work with rather early on. I was really lucky that Kimberly Phillips has similar interests as I do in terms of exploring the weirdness of Vancouver’s identity and its confusion.

For example, 23 Days at Sea was an exhibition of artists doing residencies on ships. That is so genius, because it speaks to Vancouver’s absurd lack of space. I contacted a few different galleries and was really pleased to find that Kimberley Phillips had such a dynamic vision. She’s been as much a mentor to me as the teachers in my program.

When I first moved to Vancouver and told people I was going to work in arts, they said, “oh, well Vancouver doesn’t really have an arts scene. You should go to Toronto.” But I think about that now, and it seems so bogus. Maybe our art scene isn’t as easily detectable, but there’s a lot of stuff going on.

MJ: I think it can be a bit inaccessible, if you’re not already in those circles.

AT: Yeah, you definitely have to want it in order to get into it. I think it’s confused similar to Vancouver’s identity.

MJ: Can you speak more to the theme of the show?

AT: I wanted to do a show after I recognized something about the local art scene from talking to artists. I noticed that photography in Vancouver was often exhibited in a way that set it up as the legacy of this Vancouver School tradition, or as rebelling against it. I saw that as a disservice to artists who see that “legacy” as totally irrelevant. If you practice photography in Vancouver you’re not necessarily thinking about Jeff Wall all the time.

Initially I had a really eclectic selection of ten photographers, and my idea was to take several works from Vancouver and essentially show that they don’t immediately gel together. But then that becomes really difficult because it still defines these artists in negation to the Vancouver School, still in that negative dialectic.

So then I had to whittle it down to seven artists, and I was asking, what are these artists doing in their own rights—and it doesn’t have to be cohesive, but it has to speak to all of the pieces. Abstraction came out of that. It was really interesting. Not formal abstraction, because a lot of it is realism, but it speaks to the increasingly abstract engagements that we have in our day to day lives.

I think Vancouver is a city of abstractions in a lot of ways. The definition of abstraction that I’m working off is the basic idea of taking away something to create a kind of removed experience, and that’s so pertinent to our age right now. How we talk, in person and on social media, it’s so abstracted now.

The title, Three Kinds of Abstraction, comes from this really great George Baker essay about photography and abstraction. People so often think about abstraction as just formal abstraction, but with the title Three Kinds of Abstraction, I wanted people to consider what else we could be referring to if not formal abstraction. What is abstraction? When I started down this road, I didn’t really know what is was, beyond Rothko, so that was the idea behind the title.

MJ: I very rarely think of abstraction as anything other than in formal terms. But you’re very right, it’s evident in the ways things become isolated and disjointed.

AT: Or things can be increasingly abstracted from their origins, but their original state was abstract to begin with. George Baker talks a lot about finance capital, and how you can make money from money, and that’s so abstract because money in itself is abstract. His whole thing is that photography is moving in this direction of being an abstraction of an abstraction because a photograph in itself is an abstract representation of time and space.

MJ: How long will the show be up for?

AT: It wraps up on the 27th of August. There’s a few programming events, so there’s a panel discussion on August 4th between Helga Pakasaar, Ian Wallace, and Ed Spence, which I will mediate. I’ll also give a curator’s tour on Saturday, August 13th at 2pm.

MJ: Does that terrify you? Giving talks?

AT: I’m okay with guided visits and things, but I’ve never mediated a panel before, which seems like a really delicate operation. So I’ve been watching MoMA panel discussions to practice.

atch the opening reception of April's show tomorrow, July 29th, at Access Gallery. See you there!