Interview: Patrick Kyle

/Patrick Kyle is a Toronto-based illustrator, comic book artist, self-publisher, and aspiring risograph master. His previous comic book series, Black Mass (Mother Books, 2012) and Distance Mover (Koyama Press, 2014), were nominated for Doug Wright and Ignatz awards, respectively, and his most recent publication Don’t Come in Here (Koyama Press, 2016) promises to do even better. In this first longform graphic novel, Kyle captures the strange, disorienting, and sometimes hallucinogenic realities of apartment living—realities we in Vancouver have come to know and love (or at least tolerate).

As Kyle geared up to head to the Toronto Comic Arts Festival—the next stop on his whirlwind North America book tour—we called him up to ask him all about Don’t Come in Here, old school printing techniques, and his upcoming event at Vancouver’s own Lucky’s Comics on May 19, 2016.

Patrick Kyle, photo by Matthew James-Wilson

SAD Mag: Tell me a bit about Don’t Come in Here. What motivated you to do this book?

Patrick Kyle: Before I started working on Don’t Come in Here, I’d just kind of been known for making small art books and mini-comics. I’d never embarked on anything like a full-blown graphic novel before. So it was my first foray into trying to figure out how to make that work.

SM: Your other books (Black Mass and Distance Mover) aren’t full graphic novels?

PK: They’re collections of mini-comics. My intention with those was to have some sort of ongoing narrative between them, they were sort of serialized, and I think they read less as complete stories. I guess Don’t Come in Here is my first attempt at a full thing, all together. Although it is also told in short stories, short vignettes. I’m most content with this book. I feel like it’s my most complete work and definitely my most accessible work to date.

SM: Was it difficult making the switch to longform?

PK: Previously, I never really did any preliminary work. I would just kind of go for it: stream of consciousness, just a blank sheet of paper and a brush. That’s how my comics would go. And that’s a lot of fun, but because I wanted to make something that would be more accessible and readable, with this book I did a lot of preliminary work and thumbnails and writing and sketches and stuff like that.

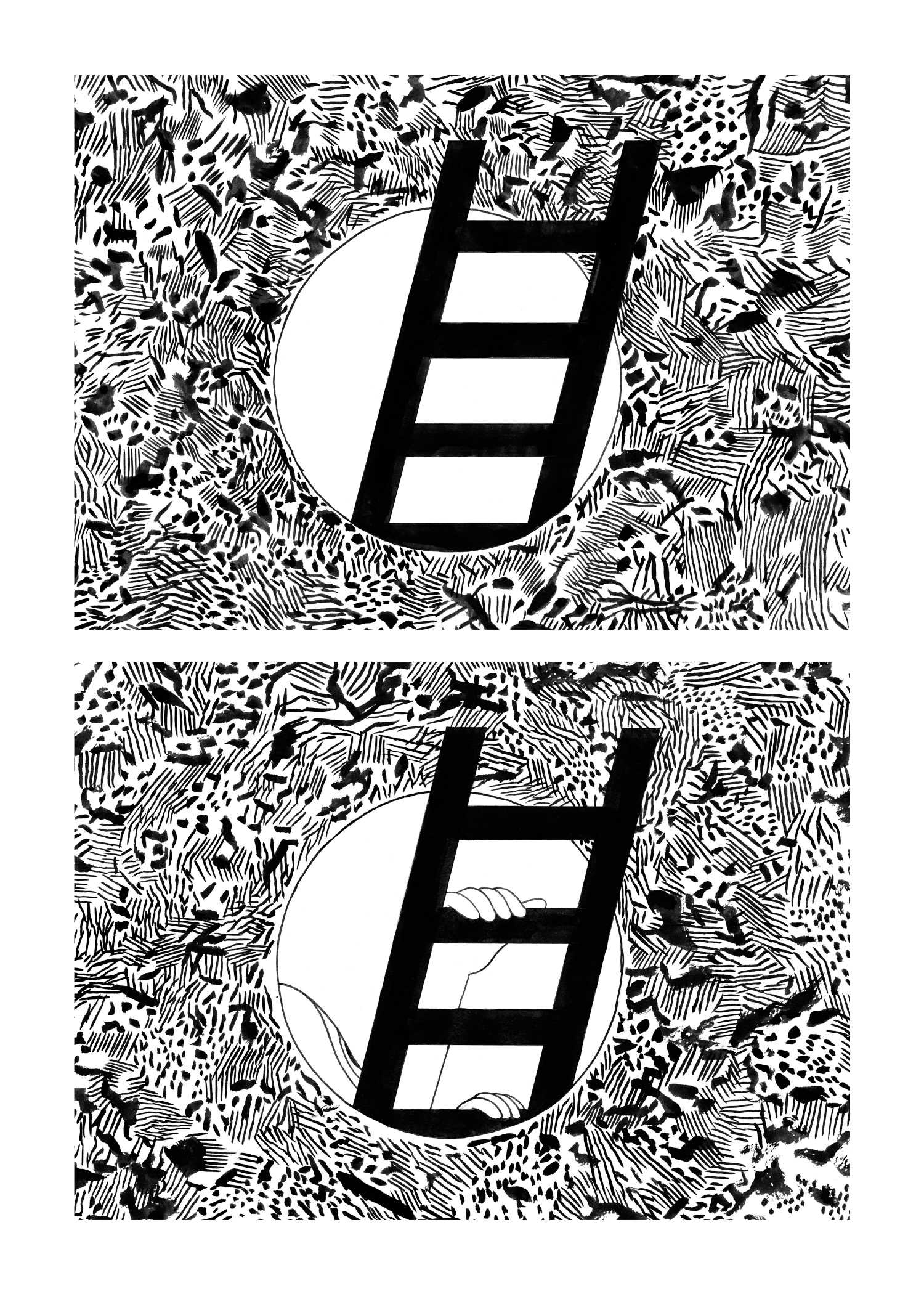

Excerpt from Don't Come in Here

SM: Don’t Come in Here definitely looks different from some of your other work, which is so colourful and vibrant. Why did you choose to go all black and white this time?

PK: Actually, I really prefer working in black and white. I would see all of my stuff as black-and-white art, because most of it just exists between me and my drawing board. When I was in university, I was doing more analogue media and painting, but as I became more of an illustrator, and started getting more work as an illustrator, I made the switch to colouring more of my work digitally—just for time, to make the process a little easier. Using the computer, I brought a lot of vibrant colours into my work that way. So, yeah, I didn’t really feel like it was that big of a change.

All of the work in my previous book, Distance Mover, was all drawn in black and white as well. The colour part came into play when I printed it. I printed that one on my risograph at home.

SM: Distance Mover was self-published?

PK: Sorry, the self-published issues of Distance Mover I printed at home with the risograph, but the collection was printed by Koyama Press. The Koyama version was two colour. It sort of mirrors the risograph aesthetic, but we just chose two colours throughout the whole book.

SM: Why do you like risograph printing? It’s a pretty old school, isn’t it?

PK: [Laughing] Yes. I’ve been in kind of a risograph nightmare right now. I have two machines and the Toronto Comic Arts Festival is this weekend. I have to kind of scramble to get things going and I’m having issues with machines. Because they’re definitely pretty old, and you definitely run into a lot of problems. Unless you’re like a dedicated copy technician or whatever, you probably don’t know how to fix them. I definitely don’t know how, unfortunately.

But when they do work, it’s amazing. It’s really inexpensive to print with them. The ink is cheap and the effects you can get with them are fairly comparable to screen printing, with not as much work. It’s really quick as well. You can get a lot of really great effects. It’s sort of like in between offset printing and screen printing—somewhere in the middle.

SM: I noticed a similar kind of tension between analogue and digital in Don’t Come in Here, especially in the way the protagonist relates to his computer (or, rather, how his computer relates to him). How much of that comes from your own experiences as an artist? What was your thinking there?

PK: It was just sort of a personal. That’s where I spend so much of my time, sitting in front of the computer. The book was pretty inspired by 2001: A Space Odyssey. I was thinking about the computer in that. I just think it’s really funny, this antagonistic relationship where the computer is sort of arrogant and knows that he is greater than who he is serving. I just thought it was kind of a funny character relationship. In Don’t Come in Here, the relationship between the character and the computer sort of disintegrates as the story goes on.

Excerpt from Don't Come in Here

SM: So would you call this work autobiographical?

PK: I would say it’s more sort of inspired by my life. Like, I certainly had no psychological adventures through the wall or anything like that—yet. Not yet, at least.

But, yeah, I looked at a big apartment five years ago that was kind of big and empty and foreboding. It was just sort of this big, empty space. It made me think about living spaces and how they relate to your mental state.

SM: Did you end up renting that big, foreboding apartment?

PK: Yeah! My girlfriend and I lived there for, like, five years. It was just a big apartment with five rooms and a kitchen and a bathroom. And it was just kind of strange; no one had lived there for, like, fifteen years before we moved in. The landlord was this 90-year-old man and he was hesitant to let anyone move in there, but my girlfriend kind of wooed him and he allowed her to move in.

It was a fantastic space for creating art and stuff. We had a lot of space to do weird media experimentation, to build sculptures and things like that. But it was also really sort of haunted. It was really old and just kind of dilapidated, and because I’m an artist and I don’t really go out much, I felt like I was really haunting the place—just wandering around it trying to get things done.

SM: Is that why you left? Because of that haunted feeling?

PK: Eventually the elderly landlord passed away. The new landlord took over and eventually kicked us out under weird circumstances. He told us that his mother was moving into the apartment and he needed it for that. It really affected us; it was a real loss. We ended up writing him this really long letter begging him to let us stay. We didn’t really understand why. Of course, it was just about money, and we ended up moving out.

SM: Wow, that sucks. But such is life, I guess.

PK: Yeah, totally. That’s what the landlord said to us: “This is life. Sorry.” The landlord character says that in Don’t Come in Here when he’s ejecting the character out of the apartment.

SM: Yeah, that was so harsh!

PK: [Laughs]. Yeah.

Excerpt from Don't Come in Here

SM: I also noticed a lot of contrasts in the book. Between small spaces and large spaces, interiors and exteriors, “normal” functioning and psychedelic hallucinations. Was that intentional? Or is that just my Arts Degree talking?

PK: I mean, part of my intention with the book was to leave it open to interpretation. A lot of the things that I enjoy most are kind of ambiguous in nature. I like allowing an audience to get what they will, take what they will from a work. I hope that people will be engaged in Don’t Come in Here in that way.

But for me, it was just really trying to illustrate my day-to-day mental state. I was thinking about dreams and reality and infinity and just the scary, overwhelming concepts that eat away at me—the general mundane nature of life and being kind of overwhelmed and just sort of debilitated by that at the same time.

SM: Can you tell me a little bit more about your self-publishing imprint, Mother Books?

PK: It’s just part of my practice. I bought a risograph machine two years ago and I just kept with it. It’s just really satisfying for me. I really like the immediacy of it, being about to finish a work and then be able to immediately do the printing process. I’m sort of impatient; I like completing the work quickly and then moving onto the next project. The risograph machine is right behind my desk. I turn around and I’m able to just slap the artwork on there and then start reproducing it.

SM: Has the experience of printing your own work changed the way that you illustrate?

PK: Oh, yeah, definitely. The style I used for my series, Distance Mover, was tailored to a risograph aesthetic. I had to draw it in a really specific way so that the printing would work properly. So, yeah, it’s definitely informed my drawing.

SM: Is it strange, then, to be working with a publisher now? To have to adapt to that?

PK: Yeah, a little bit. But at the same time, my experience self-publishing and learning about book making has definitely helped me design my books for print and make sure that everything’s alright. Having a good understanding of that is really useful.

Excerpt from Don't Come in Here

SM: What about your day job as an illustrator? What do you get out of making comics that you don’t get out of making illustrations? Or vice versa?

PK: It’s definitely more of a challenge. I definitely have to stop what I’m doing and put on a different hat. Like the other day, I was taking apart part of my risograph. I was up to my ears in risograph ink and I got an email from The New York Times. It was an illustration job that was due by the end of the day. So I just had to stop everything, clean up my studio, and start working on it right away. Because that’s my main source of income; it just has to be done.

It’s kind of interesting. So much of my work is pretty idiosyncratic—especially my comics work. I exist in a kind of bubble, where I can kind of be uncompromising. I like to do what I like to do and that’s all there is to it. But when you’re working under an art director and they have certain expectations, you have to cater to that more. I have to be a little more forgiving when I’m working with an art director—make sure that I’m doing what they want and be a little more reasonable in that way.

SM: “A little more reasonable.” I like that.

PK: [Laughs] Yeah, everything I do, I try to make pretty weird. I like to challenge the idea of what art and design is and make people excited about it. I create images that are different from what people are used to seeing.

SM: Do people ever react negatively to that? To the quirkiness of your work?

PK: I’ve never experienced any backlash or anything. I posted like a short preview of Don’t Come in Here on The A.V. Club a few days ago, and the comments for that were brutal, obviously. Any internet comments board is just a bunch of teenagers going crazy and you know, tearing something apart.

Aside from those kinds of things, I haven’t really received a lot of negative things in terms of my approach. More often people are just like, “I don’t get it. It’s just not for me.” And that’s totally fine. My ideology with this is that as I make more and more of this stuff, and there’s more of my work out there, people will just get used to it and hopefully warm up to it as time moves on.

SM: Well, it looks like it’s working!

PK: I feel like it’s working. [Laughing]. Well, I hope it’s working.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Find out more about Patrick Kyle’s Don’t Come in Here at koyamapress.com, or meet the artist himself at his event at Lucky’s Comics on May 19, 2016, from 7-10 pm.