Interview with Poet Adèle Barclay

/Adèle Barclay's début collection of poetry was recently published by Nightwood Editions. She'll be reading in Montréal, Kingston, Ottawa, Toronto, Brooklyn, and Halifax over the next few weeks. Here she is in conversation with Vancouver-based poet Shaun Robinson.

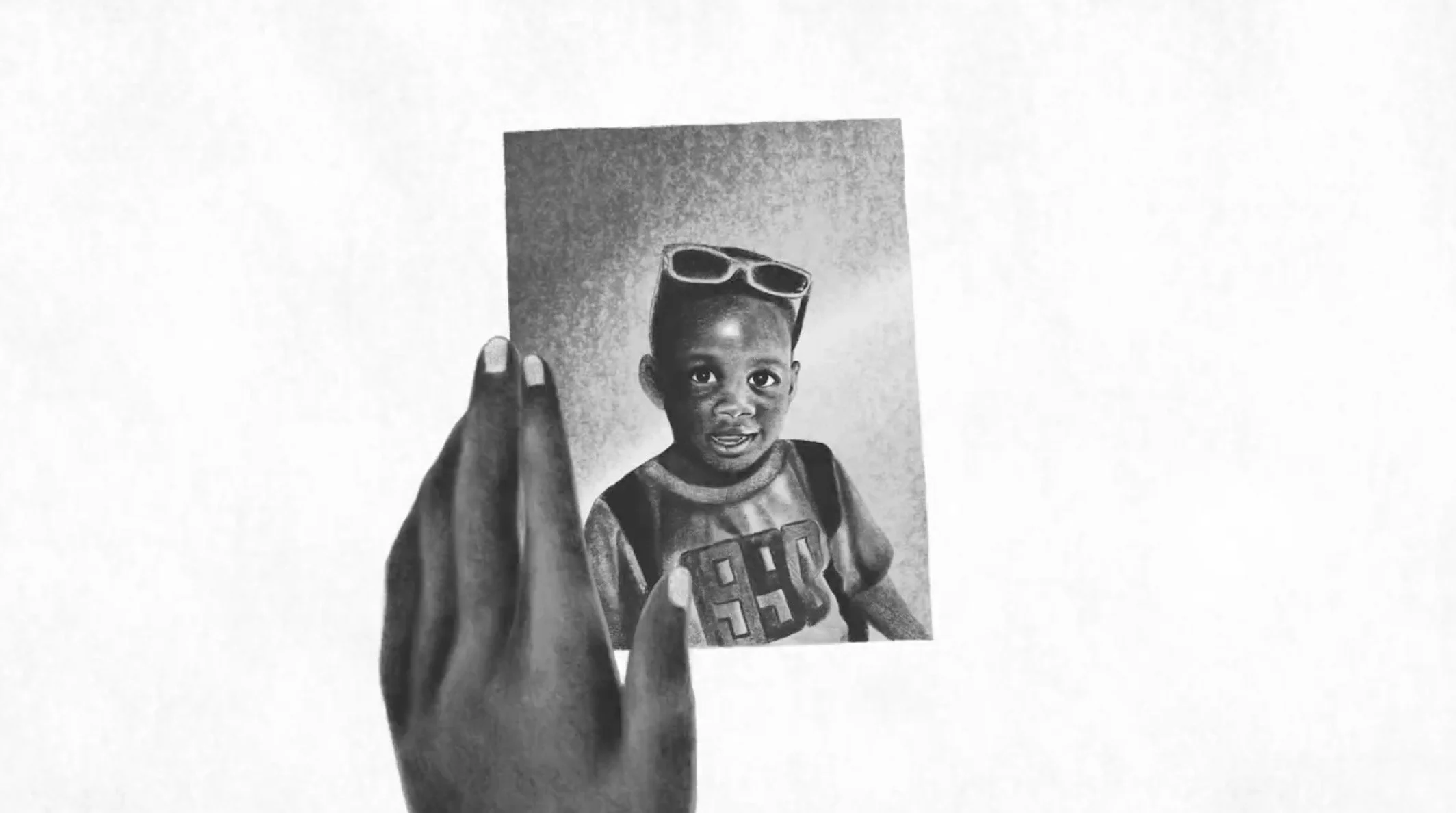

Photo by Michael Stevens

SR: Many of the poems in If I Were in a Cage I Would Reach Out to You are addressed to someone, among them the six “Dear Sara” poems that appear at the front and back of the book and at the start of each of its five sections. Do you think of these as epistolary poems, or are they rather inspired by the people to whom they're addressed? What is it about the direct address that appeals to you as a poet?

AB: I definitely think of these poems as working in the epistolary mode. The Sara poems started as permutations of letters I was writing when I was travelling and bouncing between coasts. Many of the epistolary poems are addressed to absent friends and/or lovers and they’re trying to establish the connection despite distance, parsing out and playing with the traits of a specific dynamic. I love the direct address because I am endlessly curious about people. I love the worlds we build with other people through language—how letters, poems, text messages, emails are not only evidence of our rapports, but they also actively shape them. Each relationship has its own vocabulary and texture and I like to think epistolary poems allow me to pay tribute to those idiosyncrasies. It’s also a way to conjure the addressee; it creates a wormhole that doesn’t exactly bring that person closer, but it does bring into relief that realm you’ve created together. I want to honour all kinds of relationships in poetry. Apparently I have a lot to say to my friends publicly and through irresolvable metaphors.

SR: Your book opens with epigraphs from Ariana Reines and Frank Stanford. I think of them as very different poets, but I can also see how each of them might have contributed to your work. Were they influences? Which other poets or artists inspired you in writing this book?

AB: Ariana Reines and Frank Stanford were major influences for me. And you’re right: they’re very different. Reines is an astrologer and cosmopolitan flâneuse with the brains of an academic and the heart of a troubadour. And Stanford, dubbed the “swamp rat Rimbaud” by Lorenzo Thomas, is rooted in this rural dark imaginary. And yet there are some similarities—they both revel in the abject and locate transcendence therein. Stanford is concerned with cosmic transformations too, but as they go down in his backyard. His poetry taught me that I could write about the moon and even use natural imagery, which I shied away from because I was trying to resist my Canadian-ness. Reines was an influence in real life because in a workshop she told me to let myself go, to get bloody and messy and drop overly refined conceits.

I feel like pairing these two poets gestures at some of the paradoxes I’m writing through—mundane/supernatural, rural/urban, abject/transcendent. I think of them as poets of wild transformations—their poems produce serious movements. It’s subtle but I think my collection deals with origins or rather the poems, in their obsession with places and people, hold space for how the past permeates present experience. Through Reines and Stanford I was hoping to triangulate these tensions surrounding transformation, time, and geography.

Other poets whose work got under my nails while I was writing: Dorothea Lasky—her brazen weirdness always spins me towards new worlds. She makes me clear my throat and speak up. Eileen Myles’ smart, open colloquial tone is something I tried to channel in order bring the diction back down to earth. Bianca Stone is a poet whose surreal, dense imagery always feels emotionally clear to me. I read her in the hopes that I can reach that plateau where the strange and emotionally real connect. My friends Nick Narbutas and Inès Pujos also impacted the manuscript—reading their poetry sharpened my teeth.

SR: You have a lot of great titles—for example, “Everything in Moderation Especially Spring”—that are often only tangentially related to the poem that follows. Do you have a philosophy for titling?

AB: Titles are hard! I’m glad you think I managed to nail a few decent ones. Good titles are like good tweets: they percolate for a while but seem to be made out of thin air. I’m not a fan of prescriptive titles or titles that announce the poem. One strategy I have is to identify a sub-current of the poem and riff on that because sometimes what I think the poem is about isn’t what it’s really about, so teasing out some of the peripheral streams can open it up. Oh, and I often reference artists, films, novels, music I was thinking about while writing the poems as a way to situate them. Titles, for me, feel less about summarizing or defining the poem and more about ways to locate it in literary, cultural, aesthetic, social webs.

SR: You're a Cancer, which is a water sign whose ruling planet is the moon. I haven't counted, but I'd be willing to bet that “moon” is the most common noun in the book, and water appears everywhere, in forms from oceans to ponds to rain to glasses of water. Was this deliberate, or are you just such a Cancer that these images crop up unconsciously?

AB: I pay attention to lunar cycles and use them to mark the passage of time and as prompts to reflect on certain themes in my life and what’s happening globally. And I’m also incredibly drawn to water. Being immersed in water is one of my favourite sensations. The moon and bodies of water figure strongly in my processing and interpretation of the world. Ultimately, I am such a Cancer that I move and write intuitively and so these images just appeared naturally and not overly on purpose. I appreciate this question, especially coming from you, a sceptical Scorpio.

SR: After water and the moon, I think the next most common images in your poems might be a variety of alcoholic beverages. What drink do you suggest readers consume while they read your book?

AB: If you had asked me this question a few months ago, I would’ve suggested sparkling wine or a sparkling wine cocktail like a French 75. Since we’re heading into the darker, colder months, I recommend a good bourbon, like Basil Hayden’s, rationed out slowly to pair with the collection.

You've been living in Vancouver for about a year and a half now, but you've lived in a number of other cities in the course of your writing life. Do you have any thoughts on how Vancouver's literary community compares to others in which you've participated?

I have a soft spot for Vancouver’s writing scene—it’s where I really burst out of my cocoon and the literary community has been incredibly warm and welcoming to me, which I didn’t anticipate. I think my experience is a testament to the number of fantastic writers and publishers here who work their guts out and are willing to collaborate and bring you into the fold if you also have the fire. There’s an absurdly high number of talented poets in Vancouver and there’s significant overlap between the poetry and queer scenes. Having Billeh Nickerson, Amber Dawn, Rachel Rose, Jen Currin as queer elders and poetic luminaries really lights the way. Mainstream Vancouver is so hostile: it’s the neoliberal wet dream with green-washing. In contrast, the poets take care of each other and are prone to experimentation—it feels urgent and precarious like it’s all we can do.

Shaun Robinson was born in 100 Mile House, British Columbia and now lives in Vancouver. His work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Poetry is Dead, Prairie Fire, The Malahat Review, and the anthology The City Series: Vancouver. He is the poetry editor of Prism International. His first chapbook will be released by Frog Hollow Press in the spring of 2017.