Secrets Prose: Boon Dogs

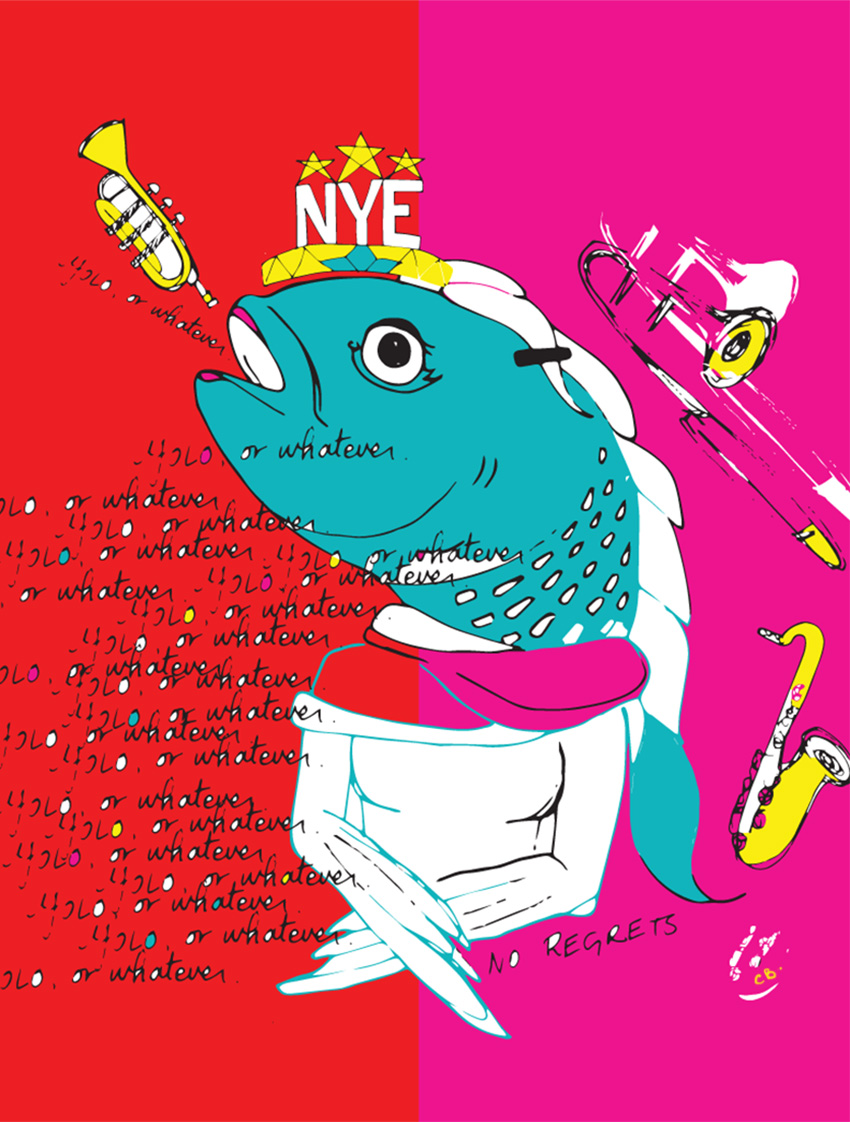

/Illustration by Ciele Beau

Boon Dogs

by Ellie Sawatzky

New Year’s Eve in a bar called The Toad. My sister Stevie and I sat in a dim corner behind the pool tables and dartboards, under a poster that read, “Beauty is in the Eye of the Beer-Holder.” I’d been drinking vodka sodas all night. Stevie was drinking Sprite.

A brass band played, six men lined up with trumpets, trombones, and saxophones. The red brick wall behind them looked pink under the neon stage lights. They didn’t sound good, but their enthusiasm was admirable.

Stevie chewed on her straw and peered up at the stage through her long bangs. “Look at the saliva,” she said. “It's free-flowing.”

“No regrets,” I said. “YOLO, or whatever.”

“Oh, to be loved like that,” said Stevie. “Not.”

This was a last minute New Year’s plan. I hadn’t even known until that morning that I’d be in Winnipeg with Stevie. She’d called me, and though she would never say out loud that she needed me, I knew by her voice that she did. I didn’t want to go—my boyfriend Jackson and I were invited to a winter bonfire at his brother’s—but I had to. I bought a ticket and came in from Kenora on the afternoon Greyhound. Stevie had wanted to go to a club called The Blink Tank, but cover was thirty dollars, so we’d nixed that. The Toad smelled like toilet and stale beer, but at least it was free.

At eleven-thirty, Stevie sucked the rest of her Sprite through her mutilated straw, then leaned back in her chair and said, “It’s like the New Year is spreading its legs.”

I took a moment to think about that one.

“You know,” Stevie said, “like—preparing to be fucked.”

I laughed because it was ridiculous, but I realized, once she’d said it, that it made sense. I had my own picture—a long prairie field blanketed with fresh snow, and all of us people, like a pack of stray dogs, about to be released onto it.

I understood Stevie, despite her relentless randomness, despite the fact that we weren’t related by blood, and we hadn’t grown up together. Stevie’s dad and my mom had started dating when she and I were in junior high. They met at a support group for people who’d lost spouses to suicide. They broke up before we even graduated high school. Neither of us had any other siblings, so we made a point of sticking together—as if we could prove we weren’t like our parents. We would never throw each other away. We knew family when it looked us in the face.

On our way to the bar for fresh drinks, a guy stopped Stevie. I couldn’t hear what he was saying over the music. His shirt had “Bear Pong” written on it, and a picture of bears playing beer pong.

Stevie’s boyfriend Erik was working a bar shift at an exclusive country club outside of town. I could have brought Jackson along to the city, but had decided against it because Stevie didn’t like him all that much. She called him “The Redneck,” and it was true—he had a penchant for trucker hats and lumberjack flannel—but he was also really sweet. For my birthday, he’d made me a birdfeeder out of a teapot.

“No thanks,” I heard Stevie say to the guy. “I’m in AA.” She caught my eye and jerked her head towards the bar. I followed. She was a shimmery fish, bare-shouldering her way through the crowd. Easily the prettiest girl in the room.

We leaned on the bar.

“AA,” Stevie said, “Abortions Anonymous.” When I didn’t react, she laughed dryly. “I don’t know why I just said that. I’m a bundle of joy tonight, aren’t I?”

“Well,” I said.

“That came out wrong,” she said. “Fuck. I should have just told him I was pregnant. That’s scary enough.”

I was the only one who knew. She hadn’t even told Erik yet.

“Just don’t think about it right now,” I said. “It’s New Year’s Eve.”

She gave me a look.

“I mean—let’s not worry about it until tomorrow.”

Stevie turned away, adjusting the feather barrette in her fair hair. The skin of her nose was inflamed around a new silver stud. She was six months older than me—twenty-three-and-a-half, technically—but everyone always thought she was younger, which bothered her because she wanted to be taken seriously. She was in her last year of an arts degree. She wanted to move to Toronto or Vancouver, she wanted to become a lawyer, an English teacher, a costume designer.

Video footage of Times Square played on the TV screen behind the bar, and everyone started the countdown. “Three—two—one.”

“Happy New Year!” I hugged Stevie.

The brass band bellowed “Auld Lang Syne.”

Stevie said, “Who’s worried?”

The following afternoon I was hungover, sitting among boxes in the radiator warmth of Stevie’s Osborne Village apartment. She lived on the fourth floor of a shabby building called “Oz,” but in a couple of weeks she’d be moving into a carriage house in River Heights. She cleaned for the people who owned the house—the McEacherns—and they’d offered it up for reduced rent and her cleaning services. The carriage house had been previously occupied by the McEacherns’ thirty-year-old son, Alex, who’d had cystic fibrosis and died from it five months earlier.

Stevie burst into the apartment wearing a vintage seafoam ski suit she got at Value Village, or “V.V.” as she called it. Her face was red and raw, her eyelashes and the hair around her face frosted white with breath. She had a to-go cup of 7-11 coffee in each hand. “You won’t believe this,” she said, “I’m waiting to pay for the coffee, and suddenly my bladder is the size of Montréal. So I go use the toilet, and I’m sitting there looking at the fucking—you know, the little Koala baby on the baby changing station. And then I notice someone’s scratched off the ‘c’ in ‘changing.’”

“Baby hanging station?”

Stevie looked somber. “What do you think, is that a sign?”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Is that coffee?”

She handed it to me and started down the hall, stripping out of the ski suit.

I followed her to the kitchen, watched her poke at the Zip-Locked blocks of basil pesto that were thawing in bowls of warm water. She put a pot of water on the stove for spaghetti, scattered pine nuts on a cookie sheet. She had an authoritative air about her. I half-expected her to turn around and tell me she was thinking about becoming a chef.

We sat down to eat at the IKEA dining table in the living room. It was even colder outside than the day before, but sunlight from the south-facing windows glowed in warm parallelograms on the floor.

“I’ve been thinking,” Stevie said. “It could actually work out nicely.”

“What could?”

“Alex was the McEacherns’ only child—so my child could be like a pseudo-grandchild.” She shook salt on her spaghetti, nonchalant. “And there’d be plenty of room for me and Erik and the baby when it comes.”

She paused, waiting for me to say something. She wanted me to indulge her, like I always had in the past, but this time I just couldn’t do it. I pinned a burnt pine nut between two prongs of my fork and said nothing.

“For now there’s still an extra bedroom,” she said. “The store doesn’t get much business in the winter anyways, so they could spare you for a couple months. You could come stay with me, just ‘til spring.”

I worked at an arts and crafts store called The Shrugging Crate. Stevie was right—the business depended almost entirely on summer tourists. “Maybe,” I said, and Stevie looked at me. “Sure.” I shrugged.

“I just hate to think of you out there,” she said, “alone in the boon dogs.”

This was the way Stevie had begun to talk—as if she had never lived outside the city.

“Yeah,” I said, “I hate the boon dogs. Always barking.”

Later in the afternoon, Stevie insisted on taking me to see the carriage house. The McEacherns were away for Christmas, but they’d told her she could stop by anytime. All I wanted to do was stay inside where it was warm.

“We can bring some of these boxes,” Stevie said. “Put your boots on and help me carry them downstairs.”

“It’s New Year’s Day,” I said. “Can we relax for a second?”

“I’m calling a cab,” Stevie said.

The McEacherns’ house was a monster. Stevie had told me there was a full-size dance studio inside. An eight-foot wrought-iron fence surrounded the property, with the carriage house, a little brick cottage, tucked into one corner of the sprawling yard.

Stevie only had a key for the back gate, so the cab dropped us in the alley. No other cars had passed us on the road. Everyone else in the whole city was curled up at home where they belonged. I stood shivering next to the stack of boxes while Stevie kicked at a solid snowbank with her Sorels and dug the key out of her purse. All my muscles tensed with cold, a headache squeezing the base of my skull. The snow crackled, hard-packed and slick, last year’s footprints and tire tracks preserved in ice. We needed warmer weather to soften it. A good layer of fresh snow.

“Shit.” Stevie had the key in the lock and was jiggling it around.

I shuffled over. “What’s wrong?”

“The lock must be frozen. It’s happened before.”

“Let me try.” I pulled off my mitten and grasped the key. I wiggled it until it got stuck. “Oops.”

“Goddammit.” Stevie stepped back. “If I can get over the fence I can open the front gate from inside the yard.”

“You can’t be serious,” I said. The headache was starting to blur my vision.

She half-jogged, half-slid down the alley towards the neighbours’ yard, which was enclosed by low pickets. From the neighbours’ side, a snowbank crawled halfway up the McEacherns’ fence.

“You’ll break your neck!” My breath came out in thin, grey huffs and my face felt numb. A tight ball of nausea turned itself over in the warm pit of my stomach. I ran after Stevie, but she was already up and over the pickets, struggling across the snow-crusted yard, her boots punching holes in the surface. Then she reached the fence. She tried to climb the snowbank but kept sliding backwards. “Come give me a boost,” she hollered.

I didn’t move. A few weeks earlier, after Stevie had told me she was pregnant, I’d made a list of all the things we had in common. We had similar senses of humour, we both liked quirky movies like Amélie and Big Fish, we both hated math. Then there was the suicide thing. Our remaining pieces of parents, the way we longed to mash them back together, like two halves of two different grapefruits. That failing, we pressed into each other. We were made of a lot of the same stuff, Stevie and I, but I could get comfortable anywhere and Stevie never settled. She ran blindly towards the next thing and expected me to follow. I used to think I’d never be alone as long as I had Stevie.

She made it to the top of the snowbank and began to hoist herself up.

I was on the verge of tears. “Stevie,” I said, but not loud enough for her to hear me, “please.”

It was dead quiet, the sky dark blue and getting ashy at the edges, blending into the streets and houses with their faint sprinklings of Christmas lights.

A door hinge squealed, and a woman appeared on the back porch of the neighbours’ house. She wore a fitted sweater and had her arms wrapped around her body, shielding herself from the cold. Her eyes went from Stevie to me and then back to Stevie. “Hey,” she yelled, “get down from there or I’m calling the police.”

Stevie squatted on top of the fence in her seafoam suit, a frothy splotch of colour against the drab landscape. One of her boots slipped and she caught herself just in time. I closed my eyes and tried not to picture her impaling herself on the pointed tips of the rails.

“Excuse me?” she said to the woman. “I live here.”

The woman was shaking her head. “Then why are you climbing the fence to get in?”

I had to hand it to her—it looked bad.

“I have a key. The lock’s frozen.”

“Yeah, okay,” said the woman.

“You’ve seen me,” Stevie said. “I’m here all the time.”

“I’m calling the police,” said the woman.

Stevie laughed, a series of short, sharp barks. “Oh, I’m scared.”

I knew I should have backed her up, jumped in to tell this woman that it was true, she had a key. But I just didn’t have the energy. “Stevie,” I pleaded, “come back.”

The woman looked at me, and then she stepped inside and slammed the door. I saw her at the window a few seconds later.

Stevie wobbled and adjusted her grip on the fence. She laughed again, the sound splitting the stillness, and looked at me for a reaction. My hands, inside my mittens, were rubbery cold and clenched in fists. Stevie inched herself around so that her back end hung over the McEacherns’ yard. Then she dropped, toppling backwards down the snowbank on the other side and landing with a thump. She got up quickly and brushed off her bum.

Her face bright and triumphant.

She’d gone too far this time. For so long, I had needed her as much as she needed me, so I hadn’t minded going after her. I’d traveled back and forth to the city, supported every new idea, indulged every whim. What would happen to us now?

Something unfurled inside me, something instinctual, stretching and testing the walls, and for a moment I thought I should get pregnant too. Then I could go with Stevie. We could need each other again. The idea opened up, just for a second, a long prairie field with a blanket of fresh snow, and then it squeezed closed and I returned to the dreary alley amidst a clutter of grand houses—none of which I would ever belong to. Even if that was what I wanted.

I took a step back from the fence. Stevie’s expression changed, her face suddenly blank, as if I were a stranger. She turned away.

It already felt like a memory, Stevie on the other side, running towards the big house, leaving tracks.

Ellie Sawatzky is a poet, writer, editor, and performer from Northwestern Ontario. Shortlisted for Arc Poem of the Year and twice longlisted for the CBC Poetry Prize, her poetry and prose have appeared across North America with Room, The Puritan, Prairie Fire, EVENT, the anthology Best New Poets 2014, and others. Her poem "Finlandia" won second place in FreeFall Magazine's annual poetry contest in 2016. She holds an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of British Columbia, and currently lives in Vancouver. You can find her here.

Ciele Beau is a visual artist and graphic designer based out of Vancouver, BC. She graduated from the University of Victoria with a BFA, Visual Arts Major, and is currently completing a 2D Design Certificate at Emily Carr University of Art and Design. Ciele loves working with colour, form, and themes around human experience and connection. Social Everywhere @cielebeau.